IACAlumnus_Jul_2018_online

Share on Social Networks

Share Link

Use permanent link to share in social mediaShare with a friend

Please login to send this document by email!

Embed in your website

5. 5 Issue XVIII, July 2018 96. Oman 97. Pakistan 98. Panama 99. Papua New Guinea 100. Paraguay 101. Peru 102. Philippines 103. Poland 104. Portugal 105. Qatar 106. Republic of Korea 107. Republic of Moldova 108. Romania 109. Russian Federation 110. Rwanda 111. Saint Kitts and Nevis 112. Saudi Arabia 113. Senegal 114 . Serbia 115. Seychelles 116 . Sierra Leone 117. Singapore 118 . Slovakia 119. Solomon Islands 120. Somalia 121. South Africa 122. South Sudan 123. Spain 124. Sri Lanka 125. Sudan 126. Swaziland 127. Sweden 128. Switzerland 129. Syrian Arab Republic 130. Tajikistan 131. Thailand 132. The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 133. Timor-Leste 134. Togo 135. Trinidad and Tobago 136. Tunisia 137. Turkey 138. Uganda 139. Ukraine 140. United Arab Emirates 141. United Kingdom 142. United Republic of Tanzania 143. United States of America 14 4. Uruguay 145. Uzbekistan 146. Venezuela 147. Viet Nam 148. Yemen 149. Zambia 150. Zimbabwe 151. Bermuda 152. British Virgin Islands 153. Cayman Islands 154. Kosovo 155. Montserrat 156. State of Palestine 157. Turks and Caicos Islands

11. 11 Issue XVIII, July 2018 m ichael h ershman is Group CEO of the International Centre for Sport Security (ICSS) - an independent and non-profit organization at the forefront of efforts to safeguard sport. He is Chairperson of IACA’s International Senior Advisory Board, and is an internationally recognized expert on matters relating to transparency, accountability, governance, litigation, and security. Mr. Hershman is Former President and CEO of the Fairfax Group and in 2006 was appointed Independent Compliance Advisor to the Board of Directors of Siemens AG, a company with over 400,000 employees. He served as Senior Staff Investigator for the Senate Watergate Committee and as Chief Investigator for a joint Presidential and Congressional Commission reviewing state and federal laws on wiretapping and electronic surveillance. He was a member of INTERPOL’s International Group of Experts on Corruption (IGEC), and sits on the Board of the International Anti-Corruption Conference Committee (IACC). In 1993, Mr. Hershman co-founded Transparency International with Peter Eigen.

6. 6 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy a dam g raycar has been a Professor in the School of Social and Policy Studies at Flinders University Adelaide, Australia, since 2015. Prior to that, he was Professor of Public Policy at the Australian National University (ANU) and Director of the Transnational Research Institute on Corruption. Over 22 years, he has acquired extensive policy experience through senior-level posts in both federal and state government. His most recent government position was Head, Cabinet Office, Government of South Australia. Before joining ANU, he was Dean of the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers, State University of New Jersey. He is a frequent visiting faculty member at IACA.

14. 14 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy a na l uiza a ranha , a former intern at IACA, holds a PhD in Political Science from the Federal University of Minas Gerais. Her dissertation, “The Web of Accountability Institutions in Brazil” was chosen as the best of 2015. She is a researcher at Fundação Getúlio Vargas and collaborates with the Anti-Corruption Knowledge Centre of Transparency International Brazil, and holds a research scholarship from the National School of Public Administration (ENAP). Her international experience includes contributions to the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, Canada, and the Canadian Red Cross. Ana was awarded the Youth ResearchEdge Award at the 2018 OECD Global Anti-Corruption and Integrity Forum. She is motivated by great challenges, and is absolutely passionate about promoting social justice, gender equality, and fighting against corruption.

48. Publisher & Layout: International Anti-Corruption Academy +43 2236 710 718 100 mail@iaca.int Muenchendorfer Strasse 2 2361 Laxenburg, Austria www.iaca.int

21. 21 Issue XVIII, July 2018 Since June 2004, Florica is an expert at the National Anti-Corruption Directorate Romania. Between December 2011 and June 2013 she was an anti-corruption mentor at EUPOL Afghanistan, and between April and July 2016 she was a trainer for prosecutors and senior police officers in the project EuropeAid/135322/DH/SER/MD (IPD project in Republic of Moldova “Support the Pre- Trial Investigation, Prosecution and the Defence Set-Up”). In December 2016 she was a speaker at the Workshop on Financial Investigations and Asset Recovery. Since January 2018 she volunteers for legal education in the pre-university education system within the National Romanian Protocol as a representative of the National Anti-Corruption Directorate. Florica is a graduate of IACA’s Master of Arts in Anti-Corruption Studies (2012 - 2014). Legal education activities under this Protocol are carried out on a voluntary and unpaid basis, and take place during the periods set during the meetings of the Protocol Monitoring Committee. During these periods, volunteers deliver legal education training(s) at schools on subjects of interest to students and teachers, such as children‘s rights, human rights and fundamental freedoms, the consequences of their own deeds, criminal liability, general aspects regarding the national, European and international legal systems, the judiciary system in Romania, national citizenship and European Union citizenship, drug use, and corruption. According to data published on the Ministry of Justice website, on 16 April 2018, 1,033 legal practitioners volunteered to participate in legal education activities in the framework of the project (359 judges, 227 prosecutors, 87 notaries, 36 law enforcement officers, 223 legal advisors, 80 lawyers, and 21 insolvency practitioners). I was assigned to volunteer in these activities at schools. The students were very active throughout the meetings and asked questions about the fundamental rights and freedoms of children and adults provided by the Constitution, in particular about how they can prevent corruption and how to defend themselves when they encounter such problems. Given the challenges our society is facing at the moment, providing legal education and training to this target group, who can benefit from experience-sharing sessions offered by these officers, prior to their full integration into their social life, becomes an imminent need. Legal education of young people must primarily target offences of corruption and consumption of prohibited substances. It should be highlighted that corruption is a problem that affects young people and that resources misappropriated by corruption can deprive them of many rights to which they are entitled. Moreover, young people should be aware of the consequences of perpetrating corruption offences, and that such consequences may affect their entire future. To conclude, in a society where crime has reached unprecedented odds, where criminal offences occur at every corner, and where morality is no longer valued, young people must be aware that they are the ones who can change the future. For the better. Last but not least, the ability and the skills of those who are willing to train them in this spirit must be taken into consideration.

34. 34 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy P ublic trust in governmental institutions is an integral component of a democratic state where citizens rely on organizational accountability and have a right to know about the actions of state officials, as they may directly affect citizens’ lives. In many academic studies, the act of corruption often implies abuse of public office for personal profit (Mungiu-Pippidi, 2006). Despite countless resources invested in strengthening both the public and private sectors through anti-corruption reforms, enhancement of whistleblower protection, and digitalization of public services, among other measures, many countries are perceived as more corrupt than others. It is important to note here that public understanding and acceptance of corruption can differ to a great extent across the globe (Heidenheimer et al., 2002). A Short Overview on Current Whistleblower Protection in Scandinavian Legislation U NDERSTANDING OUTSIDERS by Iryna Mikhnovets

4. 4 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy 20. Botswana 21. Brazil 22. Bulgaria 23. Burkina Faso 24. Burundi 25. Cambodia 26. Cameroon 27. Canada 28. Chile 29. China 30. Colombia 31. Congo 32. Costa Rica 33. Côte d’Ivoire 34. Croatia 35. Cyprus 36. Czech Republic 37. Democratic Republic of the Congo 38. Denmark 39. Dominican Republic 40. Egypt 41. El Salvador 42. Estonia 43. Ethiopia 44. Fiji 45. Finland 46. France 47. Gambia 48. Georgia 49. Germany 50. Ghana 51. Greece 52. Grenada 53. Guatemala 54. Guinea 55. Haiti 56. Honduras 57. Hungary 58. India 59. Indonesia 60. Iraq 61. Ireland 62. Islamic Republic of Iran 63. Israel 64. Italy 65. Japan 66. Jordan 6 7. Kazakhstan 68. Kenya 69. Kuwait 70. Kyrgyzstan 71. Latvia 72. Lebanon 73. Lesotho 74. Liberia 75. Libya 76. Lithuania The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply any official endorsement or acceptance by the International Anti-Corruption Academy (IACA). No official endorsement or acceptance is implied with regard to the legal status of any country, territory, city, or any area or its authorities, or with regard to the delimitation of frontiers or boundaries. This map was produced to the best of common knowledge. 01. Afghanistan 02. Albania 03. Algeria 04. Angola 05. Antigua and Barbuda 06. Argentina 07. Armenia 08. Australia 09. Austria 10. Azerbaijan 11. Bahrain 12. Bangladesh 13. Barbados 14. Belarus 15. Belgium 16. Benin 17. Bhutan 18. Bolivia 19. Bosnia and Herzegovina S TATUS AS OF 23 JUL 2018 7 7. Luxembourg 78. Madagascar 79. Malawi 80. Malaysia 81. Malta 82. Mauritius 83. Mexico 84. Mongolia 85. Montenegro 86. Morocco 8 7. Mozambique 88. Myanmar 89. Namibia 90. Nepal 91. Netherlands 92. New Zealand 93. Niger 94. Nigeria 95. Norway IACA A L u MNI M A pp IN g

27. 27 Issue XVIII, July 2018 Queen Kashimbo- c hibwe (Zambia) holds an MA in Peace and Conflict Studies from the Copperbelt University under the Dag Hammarskjold Institute of Peace Studies (CBU, DHIPS, Zambia). She currently works as a Senior Community Relations Officer at the Anti-Corruption Commission in Zambia. In her current job, she also represents Zambia as a Liaison Officer for the Commonwealth Africa Anti-Corruption Centre. Queen is also a development expert as she holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Development Studies obtained at Zambian Open University. She participated in the IACA Regional Summer Academy- Eastern Africa in 2016, IACA Anti-Corruption in Local Governance Training 2017 and the 4 th IACA Alumni Reunion in 2017. Among the prominent figures who gave support to the conference by holding speeches and specialized presentations were former South African President Thabo Mbeki and Nigerian playwright, political activist and 1986 Nobel Laureate Prize Winner Professor Wole Soyinka. Professor Soyinka expressed hope that African Anti- Corruption Agencies would do their best in following up and tracing all resources that were stashed in foreign lands, adding that in most cases some former leaders were responsible for the corruption that the continent was facing. He observed that if such leaders would get away with it scot-free, the fight against corruption and other economic crimes would not be won. For eight years in a row countries from Commonwealth Africa have been meeting to identify ways of improving the fight against corruption and other economic crimes. This year, the Commonwealth Secretariat, which is the major funder of this annual conference, challenged the various African countries present to share their experiences in asset recovery and its returns. The meeting was officially opened by the Vice President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Professor Yemi Osinbajo. Professor Osinbajo passionately spoke of how Africa loses billions of dollars through the loot of financial resources. He noted that the continent loses over one billion US dollars annually due to crimes that involve more than one country through conspiracy acts. The Vice President urged African countries to fight transnational crimes with vigour and ensure that all assets that belong to the continent are brought back for the development of Africa. Professor Osinbajo added that Anti-Corruption Agencies in Commonwealth Africa should take advantage of already existing international instruments to trace hidden assets and ensure that such are fully recovered and returned to their countries of origin. Commonwealth Secretariat Secretary General Patricia Scotland also spoke at the conference. Making her official opening remarks for the conference, Ms. Scotland said that on a global scale, the world was facing a fierce Tsunami in the form of corruption. Ms. Scotland explained that corruption was ravaging Africa and, if left uncontrolled, it would obscure any prospects of a secure future for the continent. She noted that tackling corruption should be a priority area for the continent if wealth is to be taken back into the hands of the common people. Ms. Scotland expressed her concerns about the increasing damage that corruption was causing to the African continent. She noted that the scourge robbed the continent’s children of the funds needed to finance schools and to buy the food that the children need for them to grow strong to meet development and educational milestones. The looted funds would also meet the housing, infrastructure, energy and fair systems which will see children clear their tender years into a prosperous and safe future. Ms. Scotland stressed that the Commonwealth Secretariat is committed to ensuring that all resources looted away from Africa should be brought back, adding that her organization has put in place measures to ensure the return of stolen assets.

35. 35 Issue XVIII, July 2018 i ryna m ikhnovets , started her research at IACA in April 2018 with a focus on the interconnection between corruption and migration. Prior to joining IACA, Ms. Mikhnovets has worked as a public servant within the Swedish authority for social security and welfare, prior to which she conducted an internship at the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy in Vienna, focusing on research on the Eastern European Partnership. Her previous experience in migration includes working with young refugees at an asylum centre and in a number of integration projects for forced migrants in the southern part of Sweden. Ms. Mikhnovets also has experience of working as a volunteer for the Swedish Red Cross in an integration project for asylum seekers. She graduated with a Bachelor and a Master degree in political and social science from Linnaeus University in Sweden. The degree of exposure of wrongdoing in the public and private sectors varies greatly in European countries. One of the tools for the exposure of corrupt activities is known as “whistleblowing”, which allows individuals to support accountability by exposing wrongdoings and receiving protection against retaliation once the information has been revealed (Banisar, 2011). At the same time, reporting mismanagement within an organization can, in many cases, lead to social stigmatization, exclusion, dismissal from a position, or even risk the employee’s life. Research shows that in societies where citizens have limited or no access to public information, the private short-term cost for being honest is considered to be high, as many individuals think that it will not change general corruptive tendencies (Persson et al., 2013). According to Transparency International (TI), the act of whistleblowing involves the disclosure of information related to illegal or corrupt activities and committed within or by organizations in the public or private sector. Whether or not whistleblowing is an acceptable practice remains a topic of debate in both developing and developed democracies. Information on how much every government employee earns per year, where each citizen resides, what phone number he or she has, or what type of vehicle is registered in one’s household – all this data can be easily and freely accessed in Sweden through a number of internet platforms. Such public openness in Scandinavian countries has been in use for a number of decades and has its origins in old traditions. In fact, the renowned Swedish Freedom of the Press Act (tryckfrihetsförordningen) is the oldest in the world at 250 years old (Nordic Labour Journal, 2016). Other Scandinavian neighbours, Norway and Denmark, followed the same example much later in 1970 (Jorgensen, 2014). Constitutional regulations in Sweden and Norway stress the importance of access to information which is seen as a vital factor for democratic development (Ibid, 2014). This free access to information improves Scandinavian citizens’ trust in public institutions and often prevents conflicts of interest and occurrences of wrongdoing. The relative transparency and openness of Scandinavian countries like Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, compared to other countries across the globe, often puts them at the top of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) list ranked second, third, and sixth place, respectively (Transparency International, 2018).

30. 30 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy S tates alone through ordinary domestic approaches to law enforcement may not be able to effectively combat complex transnational crimes like corruption . The imperative need to find a solution by using all available means demands a criminal justice intervention by the international community that will be fair and even. International legal principles, i.e. complementarity and universal jurisdiction, will guide a decision on how and where to prosecute. Complementarity makes it clear that by acting against international criminals, national courts ensure the international rule of law. Thus, rather than perceiving the International Criminal Court (ICC) as an instrument of global or universal (in)justice which is disrespectful of particular African States’ sovereignty, as has been argued by many scholars , the very premise of complementarity ensures appropriate respect for States by demanding that the ICC defers to their competence and right to investigate international crimes. Only if a state is unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute a crime at the national level, will the regional African criminal chamber step in. But complementarity is a principle fraught with grey areas, interpretational difficulties, and contentious and competing policy considerations. In June 2014, the African Union (AU) meeting in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, adopted the Protocol on Amendments to the Protocol on the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. This Protocol extends the jurisdiction of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to crimes under international law and transnational crimes. The proposal to extend the mandate of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights would probably be stillborn if it were not for specific events that motivated the AU. For instance: the indictment and issuance of an International Criminal Court arrest warrant against President Al-Bashir of Sudan. For the AU, these events signified the abuse of the principle of universal jurisdiction by the concerned European states and the perceived biased and unfair targeting of African states by the ICC . A controversial aspect of the Malabo Protocol was to grant immunity not only to heads of state and government, but also to an undefined category of senior state officials. Experience has shown that on the African continent, as elsewhere, those in positions of power may abuse their authority and use state resources to commit international crimes. The Malabo Protocol envisages a complementarity relationship between the African Court of Justice and Human Rights, on the one hand, and national courts and courts of the regional economic communities, on the other hand. For crimes that have not yet reached the status of crimes against the whole of humankind, in order to align multilateral efforts cooperating in criminal matters, the argument is that regional institutional efforts seem, for now, to be more realistic than a truly international approach via the ICC. The experience of the ICC and international ad hoc and hybrid criminal tribunals shows that hundreds of millions of dollars are required for the effective and smooth running of an international criminal court . A broader understanding of complementarity i.e. the encouragement of genuine national proceedings where possible, is imperative. This will lead to (i) the best interpretation of the Rome Statute’s complementarity provision; (ii) it might save the ICC from itself; (iii) it promises a number of benefits associated with domestic trial generally; and (iv) it presents an opportunity to operationalise the African Regional Legal Framework for prosecutions and the role of civil society organisations therein . The ICC or the envisaged African Court of Justice and Human Rights does not exercise universal jurisdiction. But States do, and it is here that the real potential lies for States to not just The views I present in this paper are my own, and not that of the National Prosecuting Authority of South Africa. It is based on my research for a PhD proposal that I am working on, as well as on my experience as a prosecutor in South Africa since the 1st of February 1989.

31. 31 Issue XVIII, July 2018 supplement, but enhance the work of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights. International law does not prohibit a State from exercising jurisdiction in its own territory, in respect of any case which relates to acts which have taken place abroad. States may use their discretion to extend the application of their laws and the jurisdiction of their courts to persons, property, and acts outside their territory. The National Commissioner of Police v Southern African Human Rights Litigation Centre (SALC) and Another, 2015 (1) South African law reports page 315 (CC): The SALC submitted a dossier to the South African National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) detailing allegations of torture committed against members of the political opposition in Zimbabwe in 2007. The NPA ultimately took no action. The SALC together with the Zimbabwe Exiles Forum approached the Court to order the police to investigate. The Court found that the police was not only empowered to investigate the alleged crimes, it was bound by duty to do so. The Court found that South Africa exercised universal jurisdiction over such crimes. The presence of the suspect was not required in order to commence an investigation. The principle of subsidiarity requires that ‘there must be a substantial and true connection between the subject-matter and the source of the jurisdiction’, and that ‘the country with jurisdiction is unwilling or unable to prosecute and only if the investigation is confined to the territory of the investigating state’ . The principle of practicability requires that a State should ‘consider whether embarking on an investigation into an international crime committed elsewhere is reasonable and practicable in the circumstances of each particular case’ . The Court also all but disqualified ‘political effects’ arguments: “The cornerstone of the universality principle, in general, and the Rome Statute, in particular, is to hold torturers, genocidaires [...], accountable for their crimes, wherever they may have committed them or wherever they may be domiciled [...] Political inter-state tensions are, in most instances, virtually unavoidable as far as the application of universality, the Rome Statute and, in the present instance, the ICC Act is concerned”. [...]. ‘South Africa ‘must take up [its] rightful place in the community of nations with its concomitant obligations’, lest it becomes ‘a safe haven for those who commit crimes against humanity’ . Investigations into transnational crimes are invariably complex: (i) their ‘doubled-layered’ structure, consisting of both underlying acts and contextual elements; (ii) the specialised nature of many of these underlying acts; and (iii) complex and unique ‘modes of liability’ (such as ‘command responsibility’) that international criminal law relies on to establish criminal responsibility. Can regional efforts like the Malabo Protocol provide an effective jurisdictional and enforcement modality? Yes, if money is available and the collective political will is present. This Protocol is a positive signal in the ongoing academic debate. E ndnot E s 1 Van Vuuren “ n ational i ntegrity s ystems – Transparency i nternational c ountry s tudy r eport s A 2005”; 2 d u Plessis and Gevers ‘ c ivil s ociety, positive complementarity and the Torture d ocket case’, c ivil s ociety and i nternational c riminal Justice in Africa, c hallenges and Opportunities; 3 d ecision on the d raft l egal instruments, Assembly/A u / d e c . 52 9 ( X X111) 4 Thomas Obel Hansen, “What’s at stake as Kenya weighs withdrawal from the icc ”, The c onversation, 9 n ovember 2016 5 b ack to the future? c ivil s ociety, the turn to complementarity in Africa and some critical concerns’, c Gevers, u niversity of n atal, 2016 Acta Juridica 95; 6 s ee footnote 5 above, at page 23; 7 Paragraph 77, judgement, c onstitutional c ourt 2015 8 Paragraph 80, judgement, c onstitutional c ourt 2015 9 Paragraph 80, judgement, c onstitutional c ourt 2015

26. 26 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy I t was a highly packed conference organized by the Commonwealth Secretariat in Abuja, Nigeria from 14 to 18 May 2018, where 18 Commonwealth African countries converged to discuss the innovations needed to recover assets and other resources stolen from Africa at the height of transnational corruption and money-laundering crimes. The conference attracted 21 Anti-Corruption Agencies in Commonwealth Africa and the topic “Partnering Towards Asset Recovery and its Returns” could not have come at a better time, as the continent’s population of over 390 million people is facing slowed socio-economic growth at the hands of some corrupt individuals (Beegle et al:2016). The objectives of the conference, which is held on an annual basis in different countries, are: strengthen relations between anti-corruption agencies within Commonwealth Africa; assist delegates in acquiring a firm grasp of the value-added functions of emerging best practices and shared innovations; and assist delegates to appreciate diversity and commonality of strategies to combat corruption. This year though, the focus was on assessing and identifying effective strategies that would assist the continent to recover stolen assets and to seek continental synergies in partnering towards asset recovery. The conference was graced by high profile personalities of Africa making it a unique one. The occasion was accorded the prominence that it deserves as far as tackling corruption, money-laundering, and other economic crimes is concerned. t he author participated in the c ommonwealth s ecretariat conference as a l iaison o fficer on behalf of the a nti- c orruption c ommission z ambia for the c ommonwealth a frica a nti- c orruption c entre which is based in b otswana. by Queen Kashimbo-Chibwe C OMMONWEALTH S ECRETARIAT A SSURES A FRICAN C OMMONWEALTH C OUNTRIES OF ITS S UPPORT Recovery of Assets Stolen From the Continent

28. 28 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy She further explained that her organization had established an Innovation Hub which will be readily available to Commonwealth countries of Africa to enable them to share new and clever ways of working and delivering their mandates. She added that the Hub will also assist member countries to improve and be innovative in the way they tackled corruption through strengthened capabilities and cooperation. Former President of South Africa Mr. Mbeki was also full of optimism that the African Union Agenda 2063, which recognizes the importance of fighting corruption, was enough ground to propel African governments and Anti-Corruption Agencies to make meaningful headway in tackling corruption on the continent. The former head of state noted that African countries need to focus on having stronger institutional, national, and regional frameworks rather than powerful political leaders. He was of the view that strong institutional frameworks usually gave power to the common people which in turn make those in leadership positions accountable. Additionally, His Excellency Mr. Mbeki urged African countries to take advantage of the African Union declaration of 2018 as an anti-corruption year. He explained that this was the time for all African countries to commit themselves to fighting corruption and ensure that they adapt all international instruments on the prevention and combating of corruption for the national context. Emphasis was also placed on Africa to mobilise resources, share experiences, and agree on what each state needed to do to recover stolen assets. Mr. Mbeki noted that recovering stolen assets and resources was not an easy task and calls for assessing and reviewing existing anti-corruption policies with a view to identifying strong areas that could be implemented effectively to deter criminals from perpetuating acts of stealing resources from Africa. African countries present at the conference showcased their efforts and highlighted some of cases where stolen assets had been recovered since 2015. However, their asset recovery efforts were not without challenges. Some of these featured: delays in implementing declarations of assets laws, absence of the Proceeds of Crime Laws, an unfair playing field, absence of institutional operational independence, and the acquisition of mutual legal assistance from assisting countries, most of which were outside Africa. Others lamented the absence of asset forfeiture management mechanisms and inadequate capacities and skills to deal with asset recovery of stolen properties. At the end of the five-day conference, it was hoped that African countries that had not enacted laws against proceeds of crime would be in a hurry to do so for the continent to move forward with a common agenda of effective asset recovery and return. It was also hoped that cooperation and partnership in the tracing, recovering, and returning of assets would be strengthened in accordance with the requirements and principles of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) and the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption. The 18 countries that were present at the conference were Botswana, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, and Zambia. Queen K A s H imb O - cH ib W e WINNER OF THE IACA REGIONAL SUMMER ACADEMY - EASTERN AFRICA I MPACT S TORY COMPETITION 2016

18. 18 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy T he situation is not different in Zambia. The Construction Industry in Zambia has continued to play an important and strategic role in economic and human development. For instance, at the end of the first quarter in 2017, the Industry was third largest contributor to Zambia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) with a share of 10.8% of the total GDP . However, against the backdrop of the industries’ impressive performance and the central role it occupies in the countries’ infrastructure development agenda, corruption has continued to show its’ horrendous face in the industries’ value chain. Like other industries in the country, the construction industry has continued to experience an increase in the incidence of corruption . In response to the increased prevalence of corruption in the construction industry as well as across the industry spectrum, the Zambian government, in 2009 launched the National Anti-Corruption Policy. The policy is widely viewed as a hallmark in revolutionizing the fight against corruption. Acknowledging that corruption permeates all sections of society, the policy, among other things, prescribes a holistic approach in the fight against corruption . The policy provides for the institutionalization of the fight against corruption through establishment of Integrity Committees in both public and private institutions. Integrity Committees are charged with the task of designing and implementing initiatives aimed at cultivating ethical behavior in staff and other key stakeholders that is hard-wired to the values of an institution. This article will focus on some of the activities undertaken by the Integrity Committee for the National Council for Construction and how these activities were used to learn about contractors’ ideas on how to fight corruption in the construction industry. The activities were always interactive and as a result of this, it became clear in my mind that the participants were aware that corruption existed in the industry and that in one way or the other, they had come “face to by Kabondo Lucky Muntanga In many countries, the construction industry is key in driving agendas for infrastructure development. This is so because the industry underpins nearly all aspects of economic growth as well as human development and for this reason, it attracts huge amounts of investments. In addition to the huge sums of monies invested in the industry, the nature of the industry creates opportunities for corruption. Specifically, the uniqueness of each project, its complex multi-layered formation as well as a multi-disciplinary diverse stakeholder profile makes the construction industry prone and vulnerable to corruption. 1 c orruption and the c onstruction s ector Thoughts from a Zambian Contractor face” with it. With this realization, I have thought it safe to argue that such activities provide a better approach in enlisting the support of contractors in the fight against corruption. Activities for Integrity Committees in Zambia are guided by the Prevention, Education and Enforcement framework (PEE framework) that is promulgated by the countries’ Anti-Corruption Commission. Although the legal framework provides the main thrust for the PEE framework, it also allows the fight against corruption to be predicated on changing the behavior or mindset of people. Targeting behavioral change in people should underpin the fight against corruption because at the center of a corruption act, regardless of why it is committed, is behavior in people that is driven by an unethical mental faculty. As a member of the Integrity Committee for our organization, in the past two years I have been involved in designing and implementing awareness campaign programs for our contractors and members of staff. People and behavior have been an integral part of our awareness campaign programs. Strategically evolving around the education component of the PEE framework, the awareness campaign programs have the potential to enhance prevention and enforcement- the other two components of the PEE framework. Although I have been conducting awareness campaign programs for both contractors and my fellow employees, this article will focus on programs conducted for contractors. To ensure wide coverage of our target audience, the awareness campaign programs were conducted in ten different major geographical locations (provincial capitals). The awareness campaign programs took the form of workshops and attendance averaged 40 participants (contractors) against a target of 50. MEASURES TO CURB CORRUPTION

43. 43 Issue XVIII, July 2018 IACA AT CCPCJ As in previous years, IACA was pleased to meet many alumni as well as current students at the UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice which was held at the Vienna International Centre from 14 - 18 May 2018. In addition to an info stand, IACA staff coordinated a side event on cybercrime and cyber corruption, and speakers were represented at several events. Do come and meet us if you will be at one of the upcoming conferences and events where IACA will be present! See page 47 for details. “Anti-corruption: it starts with me and you”. This was the quotation I chose during the 2017 Integrity Forum and I fully support it.

15. 15 Issue XVIII, July 2018 C ongratulations on being awarded the y outh r esearchEdge award at the 2018 o E cd g lobal a nti- c orruption and i ntegrity Forum! c an you tell us about the topic and main findings of your research paper entitled a map of corruption control flux? Why did you choose this topic, and why do you think you were awarded the prize? The main topic is how accountability institutions in Brazil work together to control corruption cases. It was studied from a nontrivial perspective of corruption: Corruption means failed accountability, which means failed democracy. An effective web of accountability institutions fulfills the important role of reinforcing democracy and its basic inclusive condition. For the first time in the country, I launched a map of corruption control flux with a focus on the institutions at the centre of Brazil’s anti-corruption agenda, including the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, Federal Police, Office of the Comptroller General, Federal Court of Accounts, Federal Justice and the Ministries. In the literature, the argument is that despite recent institutional improvements, the final result of this web in terms of coordination is weak. From the data I collected, I concluded that Brazil’s web of accountability institutions is able to coordinate and articulate itself in order to hold public officials accountable (something new in the country), but not in a homogeneous way across all institutions (something the literature has missed). The topic chose me. The idea behind the PhD was: Brazilian institutions are able to find corruption in municipalities, but then what happens in terms of investigations and punishments? There was a widespread notion that judgements and sanctions were slow and virtually non-existent in Brazil, but no one had measured this before. I believe that my research is ground-breaking in that it proposes a new way to measure corruption - connecting it with democratic principles. It was a huge effort, following the trajectory of more than 19,000 irregularities in six accountability institutions, from 2003 until 2015. My research takes on the challenge of thinking about corruption in an applied way: how to measure it from public justifications by mayors to accountability institutions; and how to map the links and synergies among accountability institutions aimed at controlling corruption over time. D uring your career, you have been engaged in gender equality issues, particularly during your time as a researcher for the Women’s s tudies r esearch c enter of the Federal u niversity of m inas g erais ( b razil). Why is gender equality important to you, and how do gender equality issues impact the anti-corruption movement? OECD Youth ResearchEdge Award Winner 2018 a conversation with Ana Luiza Aranha

19. 19 Issue XVIII, July 2018 While I appreciate the critical role of the legal framework, policies and procedures in the fight against corruption, in my opinion, the role of culture, values and human behavior remains indispensable. The fight against corruption must start with people, their culture and behavior. Engaging contractors and sensitizing them on the causes and dangers of corruption as well as prompting them to identify measures needed to fight corruption has the potential to inculcate a culture and behavior that does not tolerate corruption. This approach removes the need to deal with resistance to change owing to the fact that contractors themselves are made to identify measures to fight corruption over which they have ownership. Another positive impact on contractors was their willingness to be agents for change by consistently promoting their anti-corruption measures in their communities. Kabondo l ucky m untanga works as Manager Internal Audit for the National Council for Construction (NCC) in Lusaka, Zambia. NCC is a statutory body that regulates the Construction Industry and builds capacity in contractors. Lucky is also a member of the Integrity Committee for the NCC. As member of the Integrity Committee, he has been instrumental in sensitizing his fellow staff as well as contractors on the causes and dangers of corruption in the Construction Industry. In this article, Lucky shares his experience from his interaction with contractors during workshops organized for them. Specifically, he will talk about ideas from the Zambian contractor on what they think are some of the measures that can be used in the fight against corruption. He participated in the IACA Procurement Anti-Corruption Training in September 2015. In addition to educating contractors on the legal framework that exist to fight corruption, discussions also focused on causes of corruption as well as on how corruption not only has devastating effects on our economy but how it can also ruin businesses and lives of contractors. In this article, I am not going to dwell on the effects of corruption but rather discuss the contractors’ ideas on how to fight corruption. Each discussion culminated into a plenary phase during which participants were invited to identify and state what they believed were appropriate measures needed in the crusade against the corruption vice in the industry. Supported by an atmosphere of openness and normally characterized by emotional moments, participants were never short of ideas on how to fight corruption. Although the overarching call from participants was the need to change the mindset of people to one that abhors corruption, common measures included (1) continuously sensitizing contractors and the general public at large on the dangers of corruption, (2) encouraging people to expose corruption and reporting culprits to relevant authorities, (3) enhancing transparency in the entire construction project tendering process and (4) introduction of digital channels to deliver services as well as automating the tendering process so as to minimize the amount of human interaction in the service delivery chain. Needless to say, the measures called for by the participants reflects their absence and represent the causes of corruption I shared with the participants during the workshops. Although the introduction of digital channels is the only measure that lies beyond the responsibility of the participants, their ability to recognize the measure readily implies the contractors’ willingness to embrace it once introduced. E ndnot E s 1 Global i nfrastructure Anti- c orruption c enter, Why c orruption Occurs (2017) http://www.giaccentre.org 2 The s tatistician (July, 2017). www.zamstats.gov.zm 3 Global e conomic c rime s urvey, Adjusting the lens on the e conomic c rime in z ambia (2017). www.pwc.com/crimesurvey 4 r epublic of z ambia, The n ational Anti- c orruption Policy (2009) C ONCLUSION

36. 36 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy Environment Act (WEA) since 2007 with an aim to empower workers to speak out about wrongdoings in the workplace and to strengthen measures against whistleblower stigmatization (Steen, 2017). The WEA added Chapter 2A in July 2017, introducing a number of new rules regarding whistleblowing and employee protection within the private sector, and employers in Norway are expected to put whistleblowing acts and whistleblower protection on company agendas (Aase, 2017). According to the new Chapter of the WEA, it is obligatory for a Norwegian company with a minimum of five employees to have whistleblowing procedures clearly stated in the company’s internal documents (Ibid., 2017). In those cases where the company consists of fewer than five employees, the routines for whistleblowing are to be prepared only if the company indicates a need for it. Starting in July 2017, “hired workers,” a category previously not included in the WEA, were given a right to speak out about misconduct in the company that hires them (Ibid, 2017). In addition, the new Chapter focuses on confidentiality and keeping whistleblowers’ identities concealed from public supervisory organs. It will help to protect employees’ identities in Norway in case they want to inform government authorities externally about any wrongdoing (Aase, 2017). Unlike Sweden and Norway, Denmark does not have an explicit national law regulating whistleblowing and whistleblower protection. Historically in Denmark, the employee’s loyalty to an employer plays an important role within the work culture and implies that the employee should not damage the employer’s reputation nor share confidential information (Reitz et al., 2007). In 2009, the Danish Data Protection Agency introduced guidelines and regulations for whistleblower schemes. These whistleblower schemes, recommended by the Danish Data Protection Authority, can be regulated by statute only in cases when these schemes are related to auditors and financial issues (Kromann Reumert, 2018). All other whistleblowing schemes not related to these regulated areas can be established voluntarily (Ibid., 2018). In 2015, the Danish Government Committee stated that there is no special need in the country to have legislation UNDERSTATING OUTSIDERS by i ryna m ikhnovets Despite the openness and trust embedded for many years in the state systems of Scandinavian countries, whistleblower protection was not a priority on the agenda and explicit legislation on whistleblower protection, including in the private sector, was only introduced quite recently. In 2016, Sweden became the first country in Scandinavia to pass a specific law on whistleblower protection which came into force in January 2017 (Sveriges Riksdag). As part of the Swedish Freedom of the Press Act there was an existing regulation for employees to communicate wrongdoing in the workplace: freedom to communicate or meddelarfrihet where the informant was protected through protection for informants or meddelarskyddet. However, no specific laws on protection of public or private sector employees were defined (Nordic Labour Journal, 2016). According to these two regulations, the employer was not allowed to punish employees or create obstacles for employees to disclose information. In addition, if an employee wanted to criticize the company anonymously, the employer had no right to find out who had spoken up (Nordic Labour Journal, 2016). These regulations were limited to public sector employees, and reporting possible wrongdoings within the public sector was not strongly criticized as citizens have a right to know about how taxpayers’ money is spent (Ibid., 2016). The private sector in Sweden showed reluctance in encouraging employees to speak out, which has led to rare public disclosures of wrongdoing. The law implemented in 2017 is expected to secure better protection for whistleblowers in both the private and public sectors and encourages employees to report on wrongdoings first internally to the respective employer, and then, in case there is no reaction, externally to the media and relevant government bodies (Ibid., 2016). In some cases, the act of wrongdoing can be reported directly through an external channel such as the media, which can bring more harm to the employer. In neighbouring Norway, provisions on whistleblower protections have been included in the Norwegian Working

39. 39 Issue XVIII, July 2018 The existing literature distinguishes between several types of corruption risk assessment, which are grouped based on different criteria such as scope and level of assessment, type of experts involved, and field of implementation. Private and public sector risk assessments – initially, the focus of CRA was more on the private sector, as those methods are seen as effective instruments especially for international companies to strengthen their compliance programmes and to prevent them from corruption-related reputational and financial costs. Therefore, most of the first guides and manuals on CRA were published exclusively for private enterprises. However, the idea of applying CRA also in the public sector has become increasingly popular in recent years. In terms of technical aspects, private and public sector risk assessments do not really differ from each other as they consist of similar phases and elements, but what distinguishes them the most is the nature of the risks that public and private sector entities face in their activities (RAI, 2015). s ectoral and organizational risk assessments – when we talk about CRA, perhaps more popular are the sectoral assessments, which aim to identify systemic risks that threaten the entire sector (public procurement, health, education, etc.). In this case, all organizations, processes, and individuals within the sector are examined as a whole with the aim to determine weaknesses which are common for all actors. On the other hand, the organizational approach is used by single institutions or companies in order to disclose threats and weaknesses within its business processes and to develop an adequate response to them, which brings the process on micro level. The differences between these two types of CRA are mainly in the expenses: the sectoral level assessment is the approach which requires more time and resources, while the organizational CRA can be carried out with significantly lower costs. I n general, Corruption Risk Assessment (CRA) is a preventive tool based on the assumption that the risk of corruption is prevalent in a vast array of activities undertaken by both public and private organizations. This suggests that the purpose of this tool is to identify specific corruption risks within a system. According to Transparency International, CRA is a process for identification of weaknesses and vulnerabilities, which may create opportunities for corruption to occur (McDevitt, 2011). In fact, a full-scale risk assessment aims not only to disclose risk factors that could lead to corruption practices but also to evaluate the likelihood those practices occurring as well as the consequences for the system if the risks materialize (UNODC, 2018). What distinguishes this approach from other anti-corruption measures is that it focuses on the potential for corruption instead of the actual existence of corruption, i.e. CRA aims to prevent corruption from happening rather than to pursue already committed violations and corruption deals. This leads us to the question why CRA is such an important tool. In order to prevent corruption effectively, experts need to know how and where it happens, which requires greater knowledge about the weaknesses and vulnerabilities within a given organization, sector or country. For example, corruption practices in a small local institution might not be the same as those in the national customs authority, or the problems that a country in Southeast Asia faces could differ significantly from the problems of a Western European state. Thus, applying mainstream anti-corruption approaches to all cases without considering their specific characteristics and complexity will probably not be successful. In these terms, CRA is essential as it allows anti-corruption practitioners to disclose the major corruption threats to which a particular system is exposed and to prioritize them, which can eventually lead to developing tailored anti-corruption tools and policies. W HAT IS C ORRUPTION R ISK A SSESSMENT ? T YPES OF C ORRUPTION R ISK A SSESSMENT Efficiency is a key issue for the fight against corruption at all levels. Recent developments in the field have heightened the need for alternative anti-corruption approaches that can deliver better results. In this context, there has been a growing trend towards promoting corruption risk assessment as a tool, which can significantly improve the efficiency of anti-corruption measures. This trend is driven by major international organizations such as the United Nations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Transparency International, which in the past few years have published a number of guidelines and manuals in order to encourage governments across the world to make corruption risk assessment an essential part of their anti- corruption strategies. Based on the existing guidance materials, in this article I aim to briefly outline the key aspects, elements and steps of successful corruption risk assessment as well as to address some of the challenges for the practical implementation of those methods.

10. 10 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy Y ou were one of the first supporters of iaca and you contributed greatly to the establishment of the a cademy. h ow do you look back at these first seven years of iaca ? This process started five years before IACA was founded with the simple idea or notion that there was a lack of high level education in the area of anti- corruption. I looked at a number of major universities around the world to find out what courses were being offered in the areas of anti-corruption, ethics, transparency, and accountability. What I found was a great lack of attention to these subjects. Therefore, I wrote a proposal to create an Academy and originally presented it to Transparency International (TI). At that time, TI did not have the capacity to start a new initiative, although they were very interested. Then I brought it to the International Group of Experts on Corruption at Interpol, which I am a member of, and I discussed it with our group and again the proposal really made a lot of sense. The breakthrough came with the government of Austria and Martin Kreutner’s intervention, because not only did Martin fully support the notion of creating an anti-corruption academy, but he took it to the Ministry of the Interior in Austria and got their support. Without this support the Academy would probably never have happened. So it was a five- year odyssey before we were able to really get the Academy up and running. For me it was a dream come true. I feel so privileged to have been involved from the very beginning and I feel a special pride in what the Academy has become in such a short period of time. I think it made history in becoming an international organization in less than two years. I do not know of any other organization that was able to accomplish that mission in such a short period of time. I also think that it set a new record for bringing an accredited master’s degree programme to the forefront, so the speed at which this has happened is nothing short of miraculous and the fact that the Academy has gained this Interviewed by Ivan Zupan IACA‘s International Senior Advisory Board Chairperson and Co-founder of Transparency International a talk with Michael Hershman

16. 16 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy An A l uiz A Ar A n HA I NTERVIEW During my bachelor’s in Social Science, I joined the Women’s Studies Research Center at my home university, focusing on the gender gap regarding corruption: why women are perceived as less corrupt than men. In 2010, I won a competitive award for promoting gender equality, from the Brazilian government and the UN Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. The topic of gender equality frames my way of looking at the political world and identifying inequalities and injustices. Political scientist and feminist, Iris Young, especially her arguments about social perspectives and democratic principles, shaped the theoretical discussions in my PhD. Gender inequalities are part of social inequalities and I relate these inequalities with corruption. Corruption means exclusion: I am excluded from social policies that affect my life (a hospital that was not built, an unsafe road built with poor quality materials, etc.). But I am also excluded from a political point of view: I was excluded from political decisions that affect my life. The public interest – understood as something contingent and open – was not the point of departure for these decisions. So, I suffer a dual exclusion: as someone entitled to have access to public goods, but also as a citizen entitled to be ruled by democratic rules of decision-making. As such, women can be especially affected by corruption: given their vulnerable position in society, when rulers choose corruption they set women further away from access to social and political decision- making. Empowering women is important not because they are more or less corrupt than men, but because they are entitled to be equal citizens in a democracy. Y ou completed a research internship at iaca in 2016. h ow did the internship support you in your professional development? After my PhD, I searched for opportunities to contribute to the international debate around corruption issues. The research internship at IACA was a career-changing experience. I discovered what I wanted for my professional life: to bridge the gap between academia and the world around it. This was the “missing link” in my career. At IACA I learned that I could use my theoretical and research knowledge to help shape current policies and debates. It set my goal: to have a successful career committed to integrity and anti-corruption issues at an international level. IACA opened the door for me, and I fully embraced the opportunity. Working at IACA meant that I could meet researchers and professionals working closely with anti-corruption and integrity issues all around the world! I also learned that even with a PhD, there were some skills missing if my goal was to work for an international organization, so I decided to take a Project Management course at the University of British Columbia, Canada. Interning at IACA was a turning point for me to pursue more skills. D uring your research internship at iaca you supported the development of the i nternational m aster in a nti- c orruption c ompliance and c ollective a ction ( imacc ). What are your memories of those days, and what are your thoughts on the imacc master programme which started its first class in 2017? At IACA, I was part of an amazing team. I was responsible for identifying institutions and groups active in the anti-corruption field, and I can say that the programme IACA put together is the first of its kind and is the best anti-corruption course for the private sector.

33. 33 Issue XVIII, July 2018 But there is another darker side of the relations between ethics and compliance, in situations where ethics and compliance enter into contradiction and where complying with the law or company policy comes at the expense of one’s personal ethical standards. This is Antigone’s dilemma: the King has forbidden that her brother’s body be buried. Should she respect the King’s law, the law of the city, or her moral and religious standard that the dead should be buried? Which should she choose, compliance or ethics? There is no good choice, but she has to choose. I don’t believe the concept of integrity to be of much help for Antigone. Integrity means literally to stay in “one piece,” to be at peace with oneself and with the external world. When ethics and compliance come into conflict, it is a tragic story – a story of being torn into several pieces, of losing something in the battle. It is the sad story of Antigone, but also that of the King who loses his own son and his wife as a consequence of his bad laws and hardline enforcement. It is the sad story of whistleblowers who lose their jobs or end up as fugitives. It is the story of those who help fugitives - or illegal migrants - because they believe that common humanity should prevail. The concept of integrity therefore highlights the many positive interactions between rules and personal values in a professional context. Integrity helps us foster these interactions through communication and training for the mutual benefit of regulators, corporations, and individuals. But, at the same time, personal values constitute a complex set of standards, with potential contradictions and difficult personal choices to make. Forgetting this complexity is forgetting the very complexity and value of the human being, and risking transforming integrity into a mere hollow ideological concept. Having said that, the borders still remain somewhat disputed. For many people, integrity, understood as honesty, will undoubtedly encompass Decalogue-type injunctions such as “do not steal,” “do not lie,” and “do not cheat.” What about abuse of power? Killing by inadvertence? Being lazy at work? Dipping one’s toe into the waters of ethics and personal beliefs in a multicultural world means entering an extremely diverse, sensitive, and evolving landscape. The triad of not stealing-lying-cheating certainly has good chances of becoming a globally shared standard of personal values in a professional environment, under the banner of “integrity.” However, it is also likely to create serious misunderstandings about what distinguishes “petty and acceptable” conduct from “serious and morally wrong” conduct. The first suggested definition was derived from corporate compliance and the second one from ethics. But this second definition, by including “do not cheat,” also means “do not break the rules at the expense of others,” which of course leads back to compliance. This is not surprising, as ethics and compliance obviously have very strong links. To be more precise, integrity – and this leads to a third possible definition – is a concept used to describe professional situations where compliance has a strong ethical foundation and echo. A concept used to reinforce rule abidance by pointing to its underlying moral or religious dimension: a conceptual bridge between ethics and compliance . And speaking of bridges, one might also observe that integrity is a truly modular bridge. Its loose perimeter makes it a flexible and handy tool, which contributes, I believe, to explaining why the notion has been so appealing and successful thus far. Successful integrity tells a happy story: a story of coherence and good relations between ethics and compliance; when collective rules and individual virtue go in the same direction. This is the story that the ancient Greek concept of “kalokagathia” tells us. “Kalokagathia” literally means “the beautiful and the good”, or the ideal union in one person of all qualities in harmony with the outside world. I NTEGRITY AS A CONCEPTUAL BRIDGE by Emmanuel Breen

7. 7 Issue XVIII, July 2018 PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT Interviewed by Mariana A. Rissetto S ince you started your career as an educator in the field of criminology and corruption, what are the challenges of education in these fields? h ow has your audience changed over the years as developments have taken place in the anti-corruption field? The first challenge is that criminologists rarely study corruption since it is not a mainstream area of criminology. There are some criminologists who study police corruption or corruption in corrections. When I started researching corruption in criminology people asked: does this really fit here? Maybe corruption should be studied in philosophy and ethics, maybe in public administration, but it was not seen as mainstream for criminology. As there is no major theory of corruption in criminological theory, all of my work is very multi-disciplinary. I have tried to bring some criminological concepts and theories into my work, but I still try to work on a very broad basis of how we can best prevent corruption. With regards to the audience, I have always taught both practitioners and students. I think there is more awareness among the practitioner audiences when I teach on corruption. I have taught undergraduate, graduate, and PhD students who in many cases are totally new to corruption. I engage with practitioners such as people in government and everyone at IACA, and these are people who know about corruption and how to deal with it, and they want to improve their skills and knowledge. I like working with very senior audiences like heads of government departments, because I have been one myself and therefore I can communicate to them from the point of view of a peer. But most of all, I like talking with very junior people who have their whole career ahead of them. I can help shape their ideas, give them concepts and thoughts to take forward, and give them some conceptual tools to work with as they deal with the complex issues they will face in the future. criminology and corruption Adam Graycar interview

12. 12 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy international recognition and the support of so many countries and non-governmental and governmental organizations really shows that it has become very important in our continued fight to promote transparency and accountability through the business, governmental, and NGO sectors. D uring your extensive career in anti-corruption you worked in a variety of sectors: governments, corporates, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations. What is the experience that affected you the most and why? I worked on a number of domestic corruption issues in the United States, some of them quite significant. I was a Senior Staff Investigator with the Senate Watergate Committee, where I was exposed to a level of corruption which I had never really imagined before. That was a very important point in my life, but the experience that really set the course for my work was when I was the Deputy Inspector General at the Agency for International Development. Until then, almost all my anti-corruption work had been domestic, in the United States, in the area of police corruption, political corruption, and corporate corruption. When I took on the role of Deputy Inspector General for the US Foreign Assistance Program, I travelled around the world to some of the most desperate countries, and what I learned stayed with me all these years. I saw hundreds of millions of dollars flowing into countries to help them improve the living standards for desperate people, to build hospital facilities and schools. At the same time, I saw a good amount of this money being diverted into the pockets of autocrats and when I saw people suffering because of the lack of resources while these corrupt leaders were living in expensive homes and had expensive cars and jewelry, it disgusted me. I knew at that time that I wanted to dedicate my life to try to improve the world for those who cannot speak up for themselves. R ecently you have embarked on a new position as c E o of the i nternational c entre for s port s ecurity, a not-for-profit organization active in safeguarding sport and its core values. What made you move back from the corporate world to the third sector? All my life I have enjoyed sports. I played sports, I watch them on TV, I go to sporting events and games, my children all play sports. But frankly, I had never looked at sports as a sector, as a business, as an industry. I looked at it as entertainment. And it wasn’t until I was appointed, in 2012, to the Independent Governance Committee of FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) that my eyes were opened to sports as a major industry - in fact a trillion dollar industry - with a lack of transparency and accountability, poor governance, and with non-existent compliance. So FIFA opened my eyes to a need. The Independent Governance Committee had only been in existence for two years and at that point we could not really make the changes that we wanted to FIFA. But that experience was enough to convince me that I wanted to concentrate on trying to bring back a bit of the purity of sports, trying to bring back the memories I had of sports being a contest based on fairness and on skills, not so much on commercial activity. It is so important to me because we have children who are positively influenced by sports around the world and they see one scandal after another, whether it is doping, match-fixing, administrative corruption, sexual harassment, or abuse, and I am worried that it is going to impact the values of children in a negative way. So I am trying to restore some of the ethical values and purity in sports, really for the good of the youth in the world. W hat are the main activities of the i nternational c entre for s port s ecurity? One of the things that I took away from my FIFA experience was that unlike traditional business sectors, whether telecommunications, construction, or defense, there were no global standards or best practices for governance and compliance in sports. So I decided to help start a collective action initiative which we call Sports Integrity Global Alliance (SIGA), and this organization now has about 100 members, which include large companies that sponsor sporting events like MasterCard, and sports organizations like the Commonwealth Games, Dow Jones, the World Bank, and also the media. We brought together a wide variety of stakeholders in sports, and we have developed a set of global principles for collective action. We are asking sports organizations, sponsors, and other stakeholders to sign on to this agreement. I took this idea from my work at Transparency International, building coalitions and using an integrity pact procedure to bring various stakeholders together to agree on a set of standards. Along with the establishment of these principles, which are available online, at SIGA we are also developing a method of rating the implementation of these principles by our stakeholders. While this is a voluntary compliance effort, it will have some teeth in it because we want to assure I NTERVIEW m ichael Hershman

32. 32 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy I ntegrity is a very important word today: most companies include an integrity section in their Code of Conduct, the World Bank created an “Integrity Vice-Presidency,” and Siemens launched a global “Integrity Initiative,” just to name a few examples. But the more important the word, the more important the discussion of what it means and implies. Let me suggest three possible definitions derived from my experience as a compliance practitioner and academic. From the corporate compliance perspective, the first definition of integrity is “ abcd ” : the classic “ABC” acronym (Anti-Bribery and Corruption), plus the letter “D” standing for “Diverse other policies” (such as, for example, Anti-Fraud or Anti-Money Laundering). Integrity in this sense is a region comprised of the land of anti-corruption and that of its neighbouring countries. But which countries are included? Should insider trading be included in the integrity programme? Data protection? Anti-trust? Sectorial regulation and technical compliance? For most companies, these aspects of compliance are not included in their integrity programme, though there is no universally agreed border. However, if, for example, technical compliance failures reach a certain threshold, as in the Diesel- gate scandal, technical compliance would be seen by the general public through the prism of integrity. Hence a second definition, taken from ethics and values: integrity means honesty . To some extent this pushes the definition problem just a step further, requiring a definition of “honesty.” Already it shows that integrity is a quality of the individual rather than a collective state of things. Calling integrity into the picture means calling on the conscience and personal standards of employees and citizens, as is done notably by the OECD through its “integrity forum” (now re-named “anti- corruption and integrity forum”). Integrity as a concept refers to individual responsibility, while, on the contrary, the primary meaning of the word “corruption” is decay and putrefaction, not of the individual, but of the body politic. by Emmanuel Breen t his article was presented by Emmanuel b reen, s enior c oordinator (Professor) for c ollective a ction, c ompliance and (private sector) a nti- c orruption of iaca , during a panel discussion at the launch event for the E u i ntegrity Project on 21 j une 2018.

38. 38 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy A Brief Introduction to Corruption Risk Assessment a lex Petkov is a consultant at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s Corruption and Economic Crime Branch where he works on the anti-corruption education initiatives of UNODC. He is also a PhD candidate in Economics at the University of National and World Economy (UNWE) in Sofia, Bulgaria. His research interests are in quality of governance and corruption, in particular in corruption prevention measures such as corruption risk assessment and anti-corruption education. Alex is currently working on his doctoral dissertation on political corruption in local governance in Bulgaria. He joined IACA as an intern and has previously worked as a risks and business continuity expert at the Bulgarian National Bank. by Alex Petkov

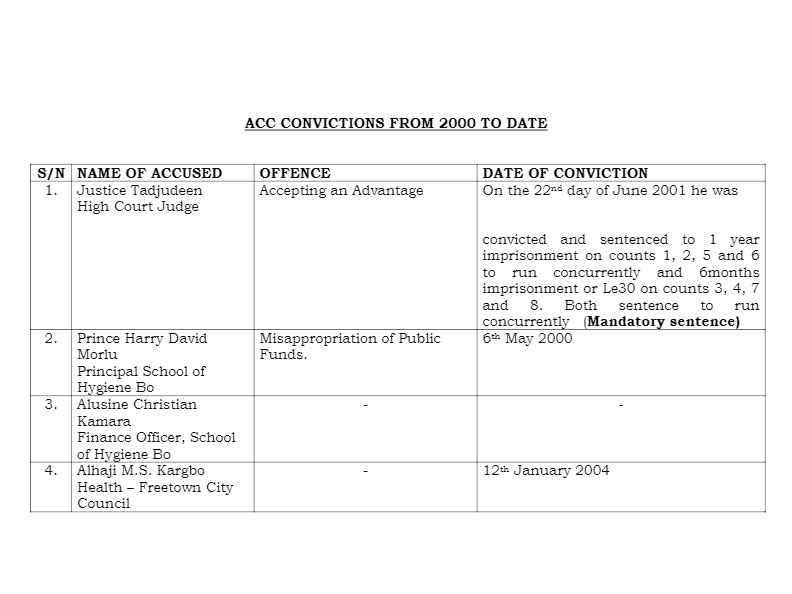

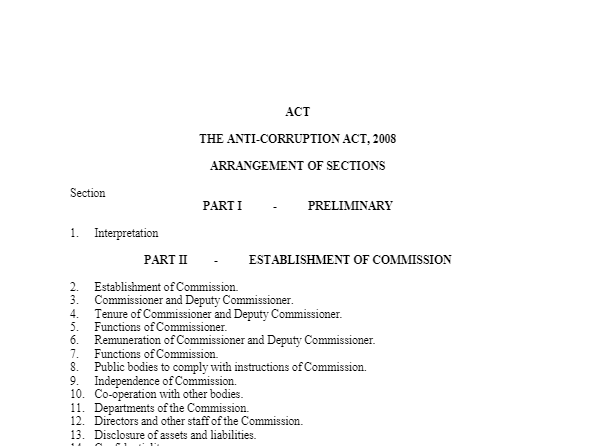

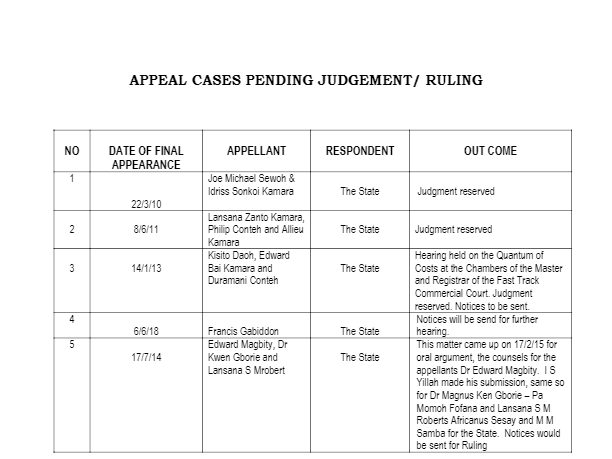

23. 23 Issue XVIII, July 2018 shows extreme weakness, too narrow to meet the country’s anti-corruption needs. Equally serious, it lacks prosecutorial powers; (Stick). Its mandate stops at investigating allegations of corruption, and refers such acts to the Office of the Attorney-General and Minister of Justice (AGMJ). Section 48(1) outlines such prosecutorial dependence: “Except where the prosecution is instituted by him, no prosecution shall be instituted under this a ct without the written consent of the a ttorney- g eneral and m inister of j ustice.” It is the AGMJ, a cabinet member, not the Commissioner, who determines prosecution. Consequently, in 2002, the then British ‘expatriate’ Deputy Commissioner complains that three quarters of 57 cases submitted had not been acted upon. Subsequently, UK withdraws support. This shows the danger of leaving prosecution for corruption in the hands of politicians. A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS A comparative analysis of the ACA 2000 and the more recent ACA 2008 clearly exposes the weaknesses of the ACA 2000. The latter increases the number of offences from 9 to 27. Furthermore, this law is UNCAC compliant. It expands the ACC’s mandate and operational independence, strengthens international and technical cooperation, imposes a mandatory assets declaration regime on all Public Officers; and grants the ACC prosecutorial powers consistent with the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), set-up to investigate causes of the war and recommends prevention of same: ... t he c ommission recommends that the acc should be permitted to pursue its own prosecution in the name of the r epublic of s ierra l eone. t he c ommission recommends that a nti- c orruption a ct 2000 should be amended to include a provision deeming prosecutions undertaken by the acc to be in the name of the r epublic. This recommendation forms a crucial part of the ACA 2008. Accordingly, Section 7(d) mandates the ACC “to prosecute all offences committed under this Act.” C ONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT To give the required legal effect to the ACA 2008, the Constitution was accordingly amended, giving the ACC exclusive powers to prosecute all corruption offences, an extreme global rarity. The Constitution of Sierra Leone (Amendment) Act, 2008 (Being an Act to amend the Constitution of Sierra Leone, 1991, so as to grant to the ACC powers to prosecute offences involving corruption). The amendment repeals and replaces subsection (3) of section 64: a ll offences prosecuted in the name of the r epublic of s ierra l eone except offences involving corruption under the a nti- c orruption a ct 2000, shall at the suit of the a ttorney- g eneral and m inister of j ustice or some other person authorized by him in accordance with any law governing the same. Further, the amendment accordingly repeals and replaces paragraph (a) of subsection 4 thereof by subsection 66: “ t o institute and undertake criminal proceedings against any person before any court in respect of any offence against the laws of s ierra l eone except any offences involving corruption under the a nti- c orruption a ct 2000.” a lhassan Kargbo is the current Deputy Director, Systems and Processes Review Department of the Anti-Corruption Commission of Sierra Leone where he has also served as Legal Officer, Head of Outreach, Chief of Intelligence, Public Relations Officer and Spokesman. He also lectures part-time at the University of Sierra Leone. He holds a Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Laws (LLB) (Hons) from Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone. He is a Senior Chevening Scholar, University of York, UK. Mr. Kargbo is a Master’s candidate, Diplomacy and International Relations, Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone. Mr. Kargbo became the first Sierra Leonean to receive the Master of Arts in Anti-Corruption Studies (cum laude) from the International Anti- Corruption Academy, Austria.

44. 44 Internat I onal a nt I -Corrupt I on aC ademy a nnouncements Attending the 2018 Alumni Reunion was an extremely beneficial experience. The balanced yet dynamic agenda and all professionals I’ve met left me enriched and inspired. I feel, without exaggeration, privileged to be part of this cohort and hope to see you next year at IACA! Neda Grozeva Senior Policy Advisor Bulgarian Institute for Legal Initiatives We hope to see you all in the a lumni r eunion 2019! m ore details will follow in an upcoming issue of the iaca lumnus magazine. For the fifth year in a row, IACA alumni gathered at the Academy on 5 and 6 July for a two-day Alumni Reunion, an annual event providing the opportunity to learn from expert anti-corruption and compliance lecturers and also extend alumni’s network with lecturers, staff, and participants and students of various IACA programmes. Thirteen alumni from different countries enjoyed sessions featuring the latest insights on hot anti- corruption issues from globally renowned lecturers. Lecturers were Michael Johnston, Charles A. Dana Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Colgate University and a pioneer in the anti-corruption field, Rebecca B. L. Li, Consultant on anti-corruption and corporate governance and former acting Head of Operations of the Hong Kong Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), Paul Myers, British investigative journalist, and Tina Søreide, Professor of Law and Economics at NHH Norwegian School of Economics. As a new feature of this year’s alumni reunion, several IACA alumni took the opportunity to share updates on their own research, work, and professional paths during structured alumni sessions which were incorporated into the overall timetable. Alumni attending the reunion also enjoyed the annual gala dinner with participants of IACA’s Summer Academy and students of its International Master in Anti-Corruption Compliance and Collective Action Programme (IMACC). IACA Alumni Reunited: Fifth Alumni Reunion in Laxenburg “