3. (14.9%) had such discussions and more men than women in pi lot areas (33.9%m; 20.2%f) and in similarly in control areas (21.5%m; 8.3%f). Focus Groups and Key Informant Interviews 1.1 Overall, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews support the findings of the survey. Citizens are aware that paying bribes is wrong, and that it is partly their responsibility to stop it. Public service officials also recognise asking for bribes wrong, but they claim that they have to do it due to shortages of money (salaries arrive late) and/or due to shortages of ma terials and/or logistics needed for them to do their jobs. 2 Such delays and shortages were blamed on central Government authorities by key informant interviewees. 2.1 FGD participants stated that it is the ‘bribe givers’ (i.e. citizens) that initiate bribery but that the ‘bribe takers’ (public officials) usually create pressure on citizens to offer bribes. The power to stop or reduce bribery is therefore in the hands of both bribe givers and bribe takers. Lower level officials were identified as more likely t o demand/take bribes 3.1 Participants stated that bribes are most commonly paid for treatment and medicines in health; enrolment grades, promotion and report cards in education; avoidance of more expensive connection charges with electricity and water; and for avoidance of fines or prosecutions for minor offences with the police. The survey supports these findings. Bribes are paid each time services are needed; they are usually paid in cash but livestock and food are also used, along with sexual favours (for fe male beneficiaries). 4.1 Citizens rarely refuse to pay bribes as they need the services. They recognise that they should report incidents to the authorities but rarely do so. Paradoxically they state that they have some confidence in refusing to pay and that with support from the authorities this would help reduce bribery. The consequences of refusing to pay bribes are noted as delays or blockages in receiving services, falling into constant trouble with the police, time wasting by officials and being hassled constantly for small offences. Conclusions The Baseline Survey demonstrates that (petty) corruption is evident across all public sectors under review. Bribe - paying is widespread, with respondents claiming that bribery is corruption and completely unaccepta ble, and that it is possibly the biggest problem in Sierra Leone. Amounts paid in bribes differ widely geographical location, rural or urban status and/or by the service required but on average petty bribe amount will always be in the region of Le 5,000 an d can (rarely) be as high as Le 250,000. For poor people particularly, this can represent a significant drain on their budgets, particularly when regular health and/or education services are needed. As a general rule, higher bribes are paid in more remote areas. Despite awareness of the unacceptability of bribe - paying, there is public sympathy with public officials’ claims bribes result from them receiving their salaries or materials with which to do their jobs. Further, few citizens were prepared to oppo se the paying of bribes and they had little knowledge and awareness of the Pay No Bribe programme. 2 For example, people have noted requests by the police for paper or pens to write a report or take notes of an interview or a meeting.

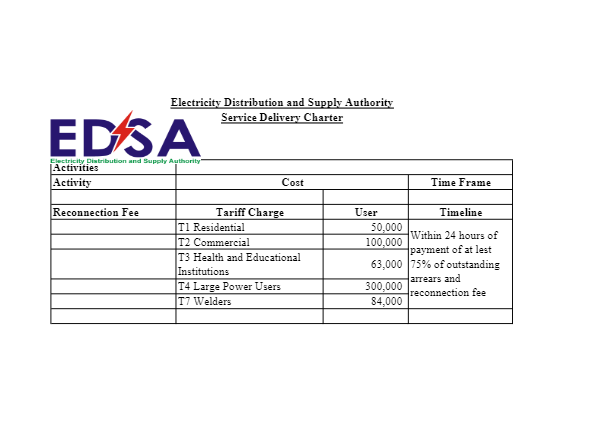

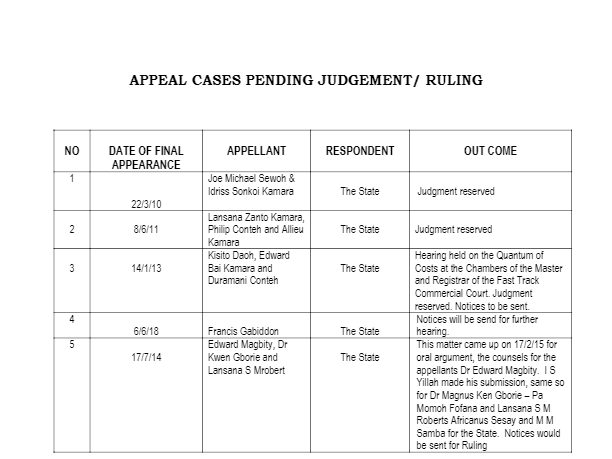

2. tap/piped water and people in remaining districts paid for water from well s with hand pumps. Outside of Western Area, most people paid less than Le 5,000, but in Western Area, 70.0% of respondents paid between Le 20,000 and Le50,000 or between Le 100,000 and Le 500,000. Impact Indicator 1: Electricity For electricity, questions focused on additional costs for (re)connection or related services paid to a national electricity generation/grid or distribution company. National electricity is available only in headquarter cities of of pilot districts and adjacent rural areas, and not in the control districts. Overall, 13.2% of respondents across pilot districts confirmed paying additional costs for electricity. Kenema district accounted for highest proportion of extra payments, while Western Area recorded the lowest (2.9%). There were marked geographical differences in amounts paid: 42.9% of respondents in Kenema paid less than Le5,000, whereas respondents in Bombali and Western Area (66.7% and 50.0% respectively) paid between Le20,000 and Le50,000 for the same services. Impact Indicat or 1: Police Questions focused on payments to police officers for assistance and/or services or problem avoidance. 1 26.1% of respondents in all pilot districts had paid a police officer, but more than twice this (57.7%) reported payments in control districts. Koinadugu district recorded the highest incidence at 64.2%. By urban/rural residence, 30.5% of respondents in urban and 21.7% in rural areas had paid police in pilot districts. Payments were largely between Le 5,000 - Le 20,000 in all areas, except Western where 60% paid above Le 50,000. Citizens’ trust in the police was lower in Western Area and Koinadugu, where more than 50% of respondents stated that they had no trust at all in the police. Across all distri cts except Kenema, more than 50% of respondents claimed to have no trust or just a little trust. In Kenema more than 20% of people claimed to have a lot of trust in the police. Outcome Indicator 3: Making a difference to corruption and effectiveness of media Questions focused on i) whether people think that they can make a difference to corruption and ii) the effectiveness of the media in revealing corruption. Results varied by district: only 18.4% of respondents in Kenema agreed or strongly agreed that ordinary people can make a difference, whereas 60.8% of respondents in Koinadugu agreed or strongly agreed. Respondents in Bo (61.0%) and Bonthe (54.8%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. Around 50% of respondents in all districts except K enema felt that the media are effective at revealing government mistakes and corruption. Output Indicator 2.3: Reporting a bribe Questions asked whether people c ould describe one or more ways of reporting a bribe. Few people were able to , given the newness of PNB, but more people in pilot areas respond ed (24.8%) than in control areas (18.7%), possibly because some ACC activities were ongoing in pilot areas. M ore men than women were able to describe ways of reporting a bribe. Output Indicator 4.2: Accessing information on corruption Questions focused on whether respondents had listened to or read information on corruption in the previous 3 months. There were differences between pilot districts (64.7% had accessed information) and control districts (27.4%) an d between men and women in pilot areas (70.3%m; 59.3%f) and in control areas (36.4%m; 18.3%f). Radio was identified as the most popular source of information. Output Indicator 4.2: Discussing corruption with family/friends Questions covered citizens who s tated they had had a discussion about corruption with family/ friends in the last three months by ( gender and pilot/control district ) . Overall, m ore people in pilot areas (26.9%) than control areas 1 For example, passing through a checkpoint or avoiding a fine or arrest

1. Executive Summary – Baseline Survey The ‘Pay No Bribe’ (PNB) Platform is a Government of Sierra Leone (GoSL) initiative, led by the Office of the Chief of Staff and the Anti - Corruptio n Commission (ACC), in coordination with relevant Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs). It is an output of the larger Anti - Corruption Support to Sierra Leone programme run by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) which aims to tackl e petty and grand corruption affecting Sierra Leone’s developmental progress. The PNB platform is an innovative reporting mechanism for citizens to anonymously report incidents of petty corruption and bribery. PNB is designed to collect real time evidence on bribery and corruption in five key service sectors: Education, Electricity, Health, Police and Focus Group Discussions Water , and to provide a useful database on petty corruption and bribery trends to support the work of the ACC and feed into evidence - based policy decision making at the government level. The baseline survey was conducted in four pilot PNB districts (Bo, Kenema, Bombali, Western Area Rural + Urban) and two control districts - Bonthe and Koinadugu. Relevant Afrobarometer Round 6 2014 - 15 s urvey data was reanalysed by district to provide information for some questions. The survey was designed to fill information gaps around specific logframe indicators, and both quantitative and qualitative methods were employed. Probability sampling techni ques were used to select a representative sample. Random selection was used at every stage and sampling was done separately for pilot and control districts. There were 720 respondents, 479 in pilot districts and 241 in control districts, approximately hal f male and half female. Age, sex, education and economic data were collected for all respondents. Many people had little or no schooling, especially outsid e of Western Area and Koinadugu and fewer women than men had ever attended school. Employment status of respondents was similar across pilot and control districts. The majority were engaged in informal activities (petty trading etc.) and i n all areas there were fewer women than men in waged work or in semi - formal skilled work such as carpentry. Baseline f indings Impact Indicator 1: Education For education, payment of bribes for school enrolment was explored. Across pilot districts, 48.6% of respondents overall confirmed having paid a bribe to place their children in schools (the highest being Bombali at 63 .6%) whilst 64.4% had done so in control districts (the highest being Bonthe at 64.7%). Most respondents had paid Le 20,000 or less. Impact Indicator 1: Health For health, questions focused on the three health services areas in public hospitals/PHUs that a re provided free under the Free Health Care (FHC) initiative. These are under - five (U5) child health care, and antenatal and postnatal care. The average percentage of people paying bribes for health services in control districts (67.2%) is almost twice th e average in pilot districts (36.6%). Among pilot districts, Bombali registered a higher percentage of respondents (57.0%) who had paid bribes , and Western Area recorded the lowest (15.0%). P ayments for health services were higher in rural than in urban ar eas for both pilot and control districts. M ore respondents paid for U5 child health than any other health service in all districts; and across all districts most people who paid bribes gave Le 50,000 or less. Impact Indicator 1: Water and Sanitation Questi ons focused on extra payments to water companies, government or service provider officials to obtain water. Control districts have almost no access to piped water. In pilot districts, 19.8% of respondents paid extra to get water, which breaks down to 23.8% urban and 15.8% rural. Urban costs were largely for water from tap/piped sources and rural costs were for wells with hand pumps. By district, people in Western Area paid mainly for