Endline Survey Report

Share on Social Networks

Share Link

Use permanent link to share in social mediaShare with a friend

Please login to send this document by email!

Embed in your website

1. Support to Anti - Corruption in Sierra Leone. Pay No Bribe – Endline Survey Report February 2019

47. 43 basis for consistency, accuracy and for completeness. Errors found were edited and corrected with the respondents in the field. The supervisor was also responsible for interviewing stakeholders (KII) and was also teamed up with one enumerator to undertake focus group discussion sessions as required. Dalan Technical Team The lead consultant did spot checks in the Western urban and rural districts to get a feel of the field work process and assisted teams resolve challenges. The lead consultant teamed up with a Dalan Associate consultant to undertake the KIIs for District Councils and for MDA representatives in all distri cts. The Dalan technical team also linked up with the district team to discuss the status of the field work and also reviewed completed questionnaires. Coffey Representatives Coffey played both a facilitating and data gathering role. Coffey represent atives visited stakeholders in advance to brief them about the upcoming survey, including the scheduled timeline to meet with stakeholders. Coffey representatives also conducted KII interviews with ACC Regional Managers and heads of CSOs supporting PNB imp lementation in the districts. While in the districts, Coffey representatives also observed some of the interviews conducted by the Dalan team members and gave feedback to improve on the quality of subsequent interviews.

4. CONTENTS / PAY NO BRIBE – ENDLINE SURVEY REPOR T 4.11. Role of the press/media Conclusion Annexes 35 36 37

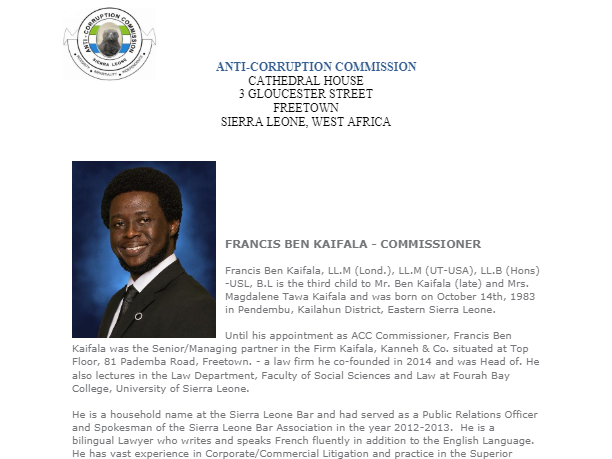

2. ABBREVIATION S & ACRONYMS / PAY NO BRIBE – ENDLINE SURVEY REPOR T Abbreviations and Acron yms ACC Anti - Corruption Commission A IG Assistant Inspector General of Police CSO Civil Society Organisations DFID United Kingdom Department for International Development EA Enumeration Area FGD Focus Group Discussion GoSL Government of Sierra Leone IMC Integrity Management Committee (in MDAs) KII Key Information Interviews MDA Ministries, Departments and Agencies PAR Progress Assessment Report PNB Pay No Bribe PPS Probability Proportional Sampling

23. 19 Figure 3.22 Comparison of baseline and Endline non - core distr icts in percentage of people thinking that the news media are effective in revealing government mistakes and corruption. Figure 3.23 Comparison of percentage of people thinking that the news media are effective in revealing government mistakes and corr uption in core and non - core districts by gender. Figure 3.24 Comparison of core and non - core district at Endline in percentage of people thinking that the news media are effective in revealing government mistakes and corruption. 3.4. Level of awareness among citizens of their roles in fighting corruption As with the baseline survey, citizens were asked whether or not they believed that ordinary people can make a difference in fighting corruption in Sierra Leone. 20 Figure 3.25 indicates that the level of awareness of whether ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption was higher at Endline than at baseline. For core districts the levels of awareness increased from 32 percent at baseline to 6 8 percent at Endline , while in non - core districts, the percentage increased from 16 percent at baseline to 73 percent at Endline . A possible reason for stronger performance in non - core districts may be related to the fact that some of the communities in th e core districts have 20 Outcome indicator 3 66.0% 72.2% 50.2% 56.8% Core districts non-core districts Male Female 58.3% 64.5% Core district Average Non-core district average

19. 15 According to a 44 - year - old male in Koidu town, Kono district, ‘’ if you now go to the police to make a complaint they will not ask you for money to buy papers and even if they want to arrest the suspect they will not ask you to provide transportation to bring the suspect. Things are now getting better because of the sensi tisation’’. A Bike rider in Pujehun reported that “In 2017 the police used to harass us too much for petty bribe, but now because they do not want to be sacked, they have minimised.” A community leader in Bonthe districts spoke about changes in the police force. He said that ‘’There is a change and much improvement compared to before or last year August especially within the Sierra Leone Police that was not doing well here, now they have changed a lot. For example, the former Local Unit commander that was here was commonly referred to as ‘envelope local Unit commander’ by citizens to reflect the fact that people felt that he took bribes...’’. Another community leader in Bo districts report that “Yes there has been a change for the better. It has reduced espe cially in the police at the checkpoints. The harassment for money has gone down a bit”. According to figure 3.17, a higher proportion of males make small payments to police than females in both core and non - core districts. The difference was between males and females in making payment to police were higher in non - core than core districts. Figure 3.15. Comparison of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to police in baseline districts and Endline core districts and non - core distric ts, Figure 3.16. Comparison of core districts, non - core districts pilot and Bonthe district at Endline of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to police. 15.98% 32.10% 14.00% Endline Core Endline non-core Bonthe

40. 36 Conclusions The Endline survey has shown that after two years of PNB implementation in Sierra Leone, there has been some progress in tackling issues of making small payments/petty corruption for services that should be free. The percentage of people across Sierra Leone paying a bribe in the 6 months before the assessment to access services in the 4 of the 6 targeted sectors has reduced in both core and non - core districts. Focus groups and KII findings suggest that citizens have increased knowledge about the services that they sho uld receive and what they should cost, and that this information is likely to have contributed to a decrease in making small payments. The media appears to have been effective in revealing information about corruption in the public sector and are an essen tial partner in any programme of this type. The majority of FGD respondents believe that ordinary people can make a difference in fighting corruption, and this is backed up by the 2018 Afrobarometer Survey. 35 A few remain unconvinced, however, largely bec ause they do not see their complaints acted upon. Some respondents are not aware of the actions that the sectors have taken in response to complaints reported by citizens, which demotivates them from reporting further. A good number of citizens think that corruption has reduced or is reducing although there are some who think that service providers (especially the police) are simply changing tactics to be less visible. Citizens’ knowledge of PNB reporting platform is good, however, and over 90 percent of r espondents who know about PNB can cite at least one way of reporting a bribe to relevant authorities. The survey shows that people listen a lot to information on corruption, but do not discuss the subject with friends and family members in quite such lar ge numbers. A future programme could focus more how to motivate citizens to take action: sensitising family and friends, encourage people to report bribery and also to refuse to make small payments for services. Keeping citizens informed about improvements to service delivery is an important motivating factor. MDA responses have been slow throughout PNB implementation, and although a good number of people think that government will act on reported cases of corruption, there is still uncertainty among citiz ens as to the kinds of changes that they might see as a result of reporting. The PNB Theory of Change relies on people reporting cases of petty corruption anonymously, MDAs receiving reports from the ACC and developing and implementing generic actions to r eform the ways in which the different sectors work. Addressing the issue of MDA buy - in from the beginning and ensuring that senior government officials engage and are seen to engage is critical. Strong public endorsements from senior ministers are helpful, and the provision of clear information about the kinds of changes that citizens could see as a result of a programme of this type, will help their expectations to remain realistic. 35 www.afrobarometer.org

16. 12 KIIs wi th local councils indicate that news of corruption may be widely broadcast in some districts. For example, a Local Council representative in Kono district said that “Anything that happens in schools is reported by pupils or parents on our two radio station s and that is where we get information about the happenings in most schools in the district. So, we have students calling in, reporting teachers that conduct extra classes outside the school to the tune Le 5,000 per class and when this happens the students call the radio and report” . They reason that such programmes make it appear like corruption is on the increase, as one incident may be narrated in several different places. Figure 3.8. Comparison of baseline with Endline in core districts and non - core districts of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months for school placement/exams/report card. Figure 3.9. Comparison of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months for school placement/exams/report card at Endline in core and non - core districts by gender. Figure 3.10. Comparison of core, non - core and Bonthe districts at Endline of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months for school placement/exams/report card. 44% 57% 43% 50% Core district Non-core districts Male Female 30.00% 43.09% 53.69% Bonthe District Endline Core Endline non-core

14. 10 Figure 3.4. Respondent’s opinion on the trend in levels of petty corruption in the health sector in Core and n on - core districts Figure 3.5. Comparison of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access health care services at a health facility at Endline , in core and non - core districts by gender. Figure 3.6. Comparison of core districts, non - core districts and Bonthe district at Endline of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access health care services at a health facility 3.2.3. Payment of bribe in the education sector. Figure 3.8 presents a comparison of percentages of people who paid bribes for school placement/ exams/report cards at baseline with those who paid a bribe at Endline in core and non - core districts. This suggests that the percentage of people payin g a bribe in the education sector increased from 20 percent at baseline to 43 percent in Endline core districts and to 54 percent in non - core districts. According to figure 3.11, around 91 percent of people reporting paying a bribe in the education sector paid for report cards. FGDs with market women and community leaders also confirmed this finding. A Market woman in Kenema stayed the same 45% pay a lot less often 32% pay a lot more often 19% Yes, there are other changes 4% 44% 57% 43% 50% Core district Non-core districts Male Female 24.00% 36.27% 44.89% Bonthe District Endline Core Endline non-core

34. 30 Figure 3.43 Endline comparison of core and non - core dis tricts in percentages of citizens thinking that the government will act on any reports on corruption in the various sectors. Section 4: Qualitative analysis; This section shows the opinion of citizens on various issues relating to the PNB project and corruption in the country. The information was collected through FGD and KIIs with various stakeholders, namely biker riders, ordinary services users, community leaders, civil society organisations, ACC staff, women’s groups, staff of local council and sen ior government officials across the sectors. 4.1. Type and levels of petty corruption across sectors. KII and FDGs suggest high levels of awareness on the concept of bribery and corruption by most respondents. They generally describe petty corruption as the way and manner in which people influence the outcome of activities or functions that reflects on performance and those actions which could be as a result of gift or small amount of money (‘token’); for example, 5,000 or 10,000 Leones received from ano ther person by the lower cadre of service providers or promises to do something after the course of action. The majority of FGD and KII respondents said they could not estimate the degree of bribery and corruption for each sector, but that it was present i n all of them. Police take bribes for traffic offences, illegal checkpoints and providing bail. In the Education sector it is usually payment for report cards, and admission to school, while in the health sector it is mainly payment for accessing what shou ld be free health care (FHC) services and drugs, (although there is some confusion over drugs that are being charged as ‘cost recovery’) . In the electricity and water sectors it is mainly illegal payments for connection and evading of charges. For judiciar y, it is mainly bribery for providing bail, altering the outcome of cases, and losing court papers to pervert justice, slow down or speed up release of detainees and confiscated property. A majority stated that petty corruption is a serious issue because it is a barrier to receiving services; service providers expecting something in return for services they should provide free. They said, the amount of bribe varies depending on the gravity of the situation but suggested that this may be as high as millions of Leones. In some instances, women may offer themselves for sexual services, while others may promise to compensate a service giver after the service has been rendered. Bribery also takes place in the water and energy sectors, but as these sectors are n ot visibly present in most rural communities, most respondents were silent on these. KIIs stated that petty corruption is mainly in the form of cash exchanges between the service user and service providers. Other common forms of petty corruption mentioned involve service providers using their office to give undue advantage to relatives/friends or to people in higher authority, to the detriment of the less privileged. Even though FGDs and KIIs indicate that this is uncommon, some respondents mentioned that sometimes women who commit offences pay bribes through sex so that they will avoid being sent to jail/prison. Some focus group participants also claimed that women may be treated less harshly than men and asked for smaller bribes or even no bribe at all. 73% 85% 7% 9% 20% 6% Core district Non-core districts Yes No Don’t know

33. 29 3.9. Citizens perception on the willingness of government to act on reported cases of corruption. The survey elicited citizen’s perceptions of the willingness of government to act on reported cases of corruption. 32 Data highlighted in figure 3.41 indicates the percentage of citizens believing that gove rnment will act on reported cases of corruption was higher at Endline than at baseline. At Endline about 85 percent of citizens in non - core districts and 73 percent of citizens in core districts compared to 39 percent of citizens at baseline believed that government will act on reported cases. PNB may have contributed to this increase, along with high profile actions taken by the new Government against corruption. As previously mentioned, the Endline survey was conducted a few weeks after the government r eleased the GTT report, so public confidence in the new government acting on corruption reports was arguably higher. A number of focus group comments reinforced this point. Further analysis showed no clear gender or age differences in this indicator. Fig ure 3.41. Comparison of baseline with Endline for core and non - core districts in percentages of citizens thinking that the government will act on any reports on corruption in the various sectors Figure 3.42. Comparison of percentages of citizens thinking that the government will act on any reports on corruption in the various sectors, at Endline in core and non - core districts by gender 32 No logframe indicator. The ACC requested the inclusion of this question in March 2017 38.7% 73.4% 85.2% 12.1% 7.0% 9.1% 49.2% 19.6% 5.7% Baseline Core Endline Non-core Endline Yes No Don’t know 73.3% 86.4% 73.3% 84.1% Core districts non-core districts Male Female

12. 8 non - core and Bonthe districts to access water services, because these districts do not have access to public or private sector managed pi pe - borne water services. The low level of petty corruption in the water sector was confirmed from both KII and FGDs reports. A community leader in Bo districts said ‘ ’even if there is corruption in the water sector it is very moderate compare to other sec tors. ’’ Another community leader confirmed the statement by saying ‘’there has not been any increasing rate in the level of corruption in the water sector.’’ Possible reason for the low level of petty corruption in water sector can be could be due to the f act that it is a small sector so administrative decision and reports of corruption are more likely to reach senior management for action than in larger sectors like health or education. Figure 3.1. Comparison of baseline with Endline in core districts of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access water. Figure 3.2. Comparison of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access water and sanitation at Endline in core districts by gender 3.2.2. Payment of bribe in Health Sector. Figure 3.3 shows that the percentage of people who paid a bribe to access health services in the 6 months prior to the survey increased from 25 percent at baseline to 36 percent in core districts and 45 percent in non - co re districts. Also figure 3.6 revealed that 11 percent and 20 percent more people in core and non - core districts respectively paid a bribe to access health care services at Endline . Analysis of FGDs also confirmed that health workers are still charging fo r Free Health care drugs or referring patients to buy the drugs from a pharmacy on occasions. A service user in Tonkolili district in said this about the health sector, “Doctors and Nurses are still receiving money for Free Health Care services i.e. corru ption. “ A bike rider also reported that “For our wives when they go to the hospital antenatal care the nurses asked them to pay money and if you don’t want to pay your child will not be cared for...”. In FGD, a service user in Makeni also reported that ‘’Whe n we arrive at the hospital, they requested for Le 40 000 and they said the lady need operation and they requested for money again. After the operation they requested for Le 50 000. So, what I kept to take care of the woman and the child, I have spent all in the hospital.’’ A community leader in Bo also reported that : ‘’yesterday my wife went to the clinic they ask her to pay for the free health care drugs and it was right in front of me the nurses were selling the drugs to other patients, so just like what my colleagues have said, I think corruption in the health secto r is on the increase.’’ In Bombali, a member of a focus group commented “... i f you ask them about the free medical, they will tell you if you are waiting for the free medical, you will have free die” . 3.79% 9.17% Male Female

21. 17 a bribe to the Judiciary in the 6 months prior to the Endline survey. 17 The lower rate in Bonthe district could be explained by the majority of people residing in riverine areas relying mainly on local courts for their legal matters; bribery is rarer in these courts compared with the magistrate and high court system predominant in most PNB core and non - core districts. Bike riders and ordinary service users in FGDs reported the following about the judiciary: • ‘’the judiciary is also second to the police in terms of corruption, for example we have most of our colleagues who are in prison for nothing, they are there under false accusation.’’ (Bike rider in Bo). • ‘’we also have an increasing rate of corruption in the local court, justice is not been given to those who deserve it.’’ (Service user in Pujehun) • ‘’The court system each time you go to the court the court clerk expect you to give him before to find your case file and call up your case, the prosecutor expect you to give him/her money or else your case will delay, magistrate also ask for money according to the gravity of the case.’’ (Community leader in Western Rural) • ‘’ For me I am more concerned about the court, I personally have seen it that to bail someone is free, but not in our own court, even when they themselves know that to bail someone is free, they still ask you to pay, because I have had a case in the court, ev en when they would have acquit you, the paper they give to you, you have to pay for it, when it is not even official and no receipt.’’(Service user in Western Rural) Figure 3.20 compares the percentage of people who paid a bribe in justice sector by gende r in both core and non - core districts. The figure indicates more males than females paid a bribe in justice sector in both and non - core communities. Figure 3.19. Comparison of core districts, non - core districts pilot and Bonthe district at Endline of per centages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access Judiciary. Figure 3.20. Comparison of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access Judiciary at Endline in core and non - core districts, by gender. 17 The figures are low generally as fewer citizens interact regularly with the justice sector 4.04% 3.61% 15.43% Bonthe district Endline Core Endline non-core 5% 19% 1% 10% Core Non-core Male Female

22. 18 3.3 Citizens perception on the extent to which the news media reveal government mistakes and corruption The Endline study assessed people’s perceptions of the extent to which the news media report government mistakes and corruption 18 involving government offici als Overall the data suggests a significant increase in people’s appreciation of the media role in revealing government’s mistakes. 19 Figures 3.21 and 3.22 present a comparison of baseline districts with Endline core districts and non - core districts respect ively, in percentages of people believing that the media are effective in revealing government mistakes and corruption. The data indicates that the percentage of people reporting that the media is effective in core districts increased from 23 percent at ba seline to 58 percent at Endline , while in non - core districts, it increased from 13 percent at baseline to 64 percent at Endline . Figure 3.23 compares the percentage of people who thought that the news media were effective in in revealing mistakes of gover nment by gender at Endline . The figure shows that more males than females think that the news media were effective in revealing mistakes of government. In core districts 66 percent of males against 50 percent of females said the media was effective, while in non - core district 72 percent of men versus 58 percent of women reported that the news media was effective. The higher figures for men could reflect their greater access to media sources such as radio and print. KIIs and FGDs both suggest that the majority of citizens have heard about PNB and other corruption issues from the radio and that radio represents the main source of information on corruption. Citizens also stated that they think that radio reports on corruption are usually accurate although a few participants commented that the programmes can sometimes be partisan. Other sources of information were bill - boards, posters and leaflets. A male community leader in Kailahun said that “ Before now, I have got information/messages on the radio about corruption and in fact, there is a giant bill board around the Clock Tower with pay no bribe messages, so I already have some information about pay no bribe campaign” A Service user in Waterloo commented as follows “Well for me I always listen to the HOT seat that AYV do present at night, because different people come to talk about what is happening in the country, about corruption and what to do about them, so we will listen and understand what is going on or happe ning.’’ Figure 3.21 Comparison of baseline and Endline core districts in percentage of people thinking that the news media are effective in revealing government mistakes and corruption. 18 Outcome indicator 1 19 This could be comp ared with Question 19C from the latest Afrobarometer Round 7 survey, once the data has been released

18. 14 • More offices now openly display their service charters. Figure 3.13. Comparison of baseline with Endline core and non - core districts of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access power supply. Figure 3.14 Comparison of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access power at Endline in core and non - core districts by gender. 3.2.5 Payment of bribe in the Police sector Figure 3.15 presents a comparison baseline with Endline figures in core and non - core districts in the percentage of people who paid a bribe to police. According to the figure, the percentage of people who reported paying a bribe to a police official at baseline was 65 percent, compared to 16 percent at Endline in core districts and 32 percent in non - core districts. This reflects a significant reduction over the period. Findings from the KIIs and FGDs suggest that because people are now more knowledgeable about petty corruption, the police find it more difficult to ask for bribes or unauthorised small payments for fear that they will be reported. Figure 3.16 compares the percentage of people who paid a bribe to police in core and non - core districts at Endline . According to the figure 14 percent of citizens in Bo nthe district, 16 percent in core districts and 32 percent in non - core districts paid a bribe to a police official in the 6 months prior to the survey. The higher percentage recorded in non - core districts suggests the need for continued citizen sensitisati on on their rights and resisting bribery. It also reflects the shorter period of outreach delivered to non - core districts through hub and spokes. KIIs with Police officers, confirmed their perception that petty corruption has reduced due at least in part t o the following actions they have taken throughout the country: • Reduction in the number of illegal checkpoints. • Police no longer taking money from complainant to take a statement. • Money no longer requested for granting bail, and posters are clearly visib le at all police stations. • Medical forms now given without payment request. • FGDs with bike riders revealed that traffic officers do not take money from drivers/riders as openly as before. 13.61% 10.00% 10.76% 2.63% Core districts Non-core districts Male Female

27. 23 Figure 3.31 Comparison of baseline and Endline in percentage of (m/f) citizens in programme areas who can describe one or more ways of reporting bribery and corruption issues. Figure 3.32 Comparison of percentage of citizens in programme areas who can describe one or more ways of reporting briber y and corruption issues, at Endline in core and non - core districts, by gender. Figure 3.33 Comparison of core, non - core pilot and Bonthe district in percentage of (m/f) citizens in programme areas who can describe one or more ways of reporting bribery a nd corruption issues 3.7 . Level of citizens awareness of anti - corruption issues In the Endline survey, citizen’s corruption awareness levels were determined by assessing the amount of information on corruption received from media and from family/friends in the last three months. 24 Figure 3.34 presents a comparison of the percentage of respondents wh o have listened/read or discussed at baseline with Endline in core and non - core districts. These figures indicate that the percentage of people listening to news about corruption was much higher than those who discussed corruption with family and friends. The percentage of people who listened to news about corruption at baseline and Endline were almost identical for core districts (73 percent). In core districts the percentage of people discussing corruption with family members and friends was slightly hig her at baseline than at Endline (33 percent at Endline and 36 percent at baseline). In non - core districts, the percentage of people listening to radio discussion on corruption increased from 27 percent at baseline to 83 percent at Endline , while the percen tage of people 24 Logframe indicator 4.1 24.8% 53.9% 18.7% 54.5% Baseline Endline Baseline Endline Coredistrict Non-core districts 61.4% 67.0% 45.8% 42.0% Core districts non-core districts Male Female 53.9% 54.5% Core district Average Non-core district average

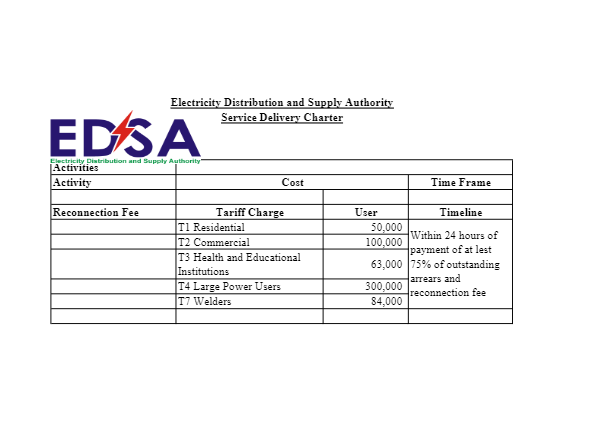

17. 13 Figure 3.11. Percentage distribution of the services for which people paid small bribes in the education sector. Figure 3.12. Respondent’s opinion on the trend in levels of petty corruption in the education sector in Core and non - core districts 3.2.4. Payment of bribe in Energy Sector Data on bribe taking in the energy sector was collected from 405 respondents living in communities with public power supply. Bonthe and other non - core districts do not have power grid so were excluded from the energ y analysis. Figure 3.13 shows that the percentage of people paying bribes to access services in the energy sector reduced from 42 percent at baseline to 12.3 percent at Endline in core districts, indicating a significant reduction in bribe payment for ener gy. This suggests that PNB sensitisation may have contributed to empowering people to say no to bribery for services. The response from the chief in Yardu (Kono) summarises the impact of PNB on people “I think PNB has helped the government to reduce corru ption and I believe if they continue like this the country will soon start developing” . A member of staff of EDSA in Bo district also reported that “the awareness raising activities have greatly increased our knowledge on corruption and very much empowere d us to resist corruption in any form. We now know what we did not know formerly.’’ Another ESDA staff in Kenema had this to say “ For EDSA, over the past one year, we were having problems in the metering system with our consumers. People bribe money to ge t meters because there was a gradual shortage of meters. We normally withdrew meters from people who delayed [paying] for their service and sell to those that bribed us. All this petty corruption has reduced with the intervention of PNB Campaign.’’ Figure 3.14 compares percentages of male and females paying bribes to access energy at Endline . The figure shows in both core and non - core districts that more males paid bribes to access energy than females. The difference between males and females was much higher in non - core than core districts. There is no clear reason for this. KIIs with MDAs and FGD with service users revealed that EDSA has seen the following changes: • Staff are now aware of the fact that taking money from customers for connection and reconnection is prohibited, • Meters are sold on the first come first serve basis and a met er repair is now free. 31.8% 6.7% 15.1% 90.8% 10.0% 27.4% staye d the same 48% pay a lot less often 34% pay a lot more often 14% Yes, there are other changes 4%

35. 31 4.2 Reasons for petty corruption. The general opinion of the respondents was that if small payments are not made to service providers, services may be delayed, provided in sub - standard manner or denied altogether. All respondents confirmed that making un authorised payment for services is ingrained in the system and that most citizens accept that they must make extra payments for services or they will not receive them. A local council staff member in Western Urban stated that “for the police, [it] is no s ecret, when you go to the police station, you will be told that bail is free but often times I have to pay. Well you will not be paying under formal ways but the other unnecessary expenditure that will come in, you will have to pay for papers and pens”. As noted earlier, whilst bike riders complain about rampant bribes demanded by police, they also agree that some payments were made in order that the police would allow them to do something otherwise illegal, like driving without licences or helmets or carry ing more people than the bike’s capacity. All bike riders confirm that they pay bribes to police in order to avoid being jailed and forwarded to court; this wastes their time and undermines their income. As one of the bike riders in Yardu (Kono) says “ yes , it depends on the situation at hand because bike riders deal with time and have their target per day. So even if you know that you are not supposed to pay any amount of money you [do] for them not to waste your time”. A senior staff of a CSO commented “ I ntegrity and accountability are lost, so petty corruption has been accepted as a norm in society”. Petty corruption is also linked to citizens not knowing their rights and the laws of the country. As a result, there is panic when confronted with a governm ent officer, including the police. Many people therefore prefer to pay a bribe rather than follow due procedure, which they may not know. A bike rider in Waterloo said that "Because of high level of illiteracy and lack of knowledge in the country, people p ay for services they should not pay for”. A number of KII and FGD comments however suggest that peoples’ knowledge levels are higher than before as a result of PNB activities. “Take for example malaria drugs are now free. The reason for this change could largely be due to the fact that people are now more aware about their rights” (male service user, Bo). “The knowledge about corruption is increasing every day and the stringent measures instituted by the new administration are very supportive in weeding o ut corrupt practices” (older male service user, Bo) . The baseline established that numerous respondents pointed out that petty corruption is a two - way act; the service user and the service provider being both responsible. If service users were to refuse t o give small payments to service providers, then service providers would not receive any benefit and the custom would cease. However, the habits of some service providers (i.e. causing delay or refusing to provide adequate services because a bribe has not been paid) still continue. One head of a CSO commented “ our systems are customised to encourage people to pay bribes, e.g. long waiting times for service, police arbitrarily stopping public transports, teachers asking for gifts as handwork, etc. ” There w as consensus among FGD respondents that, because people want a prompt service, they do not wait for due process to be followed and so bribe their way through the system. A senior manager in Waterloo (WA Rural) commented that some women may offer sex to sp eed things up. The most common reasons suggested for service provider engagement in corrupt practice were low salaries, poor conditions of service and a lack of incentive to meet the ever - increasing cost of living e.g. transport costs. It was stated that government salaries are not enough to meet service providers’ basic needs, and that a good number of trained nurses, Community Health Officers (CHO), Community Health Assistants (CHAs) and Maternal and Child Health Aide (MCH Aide) work as volunteers, are n ot employed by Government as yet and do not have any form of stipend. Some of these volunteers have been working for over 5 years without any formal employment, so they ask for small payments from patients. A volunteer in Bo stated in an FGD “I need to sur vive; I have a family to care for; I have to feed my wife and kids; I have to pay school fees for them; that is why at times I have to involve myself in these corrupt practices so that I can raise some money. Whilst corruption cannot be condoned in itself there is an understandable logic to the reality and consequences of government budget limitations

26. 22 Figure 3.29. Comparison of percentage of citizens in PNB target areas who state that it is easy or fairly easy to report a bribe via the website, ca ll centre or app, at Endline in core and non - core districts by gender. Figure 3.30. Comparison core and non - core districts in percentage of citizens in PNB target areas who state that it is easy or fairly easy to report a bribe via the website, call c entre or app, at Endline. 3.6 . Knowledge of citizens of the ways of reporting bribery and corruption issues. The survey explored respondent’s knowledge of the ways of reporting bribery and corruption. 23 According to figure 3.31, the percentage of people able to describe one or more ways of reporting a bribe increased in core districts from 25 percent at baseline to 54 percent at Endline , while in non - core districts it increased from 19 percent at baselin e to 55 percent at Endline . Figure 3.32 highlights that in core districts 61 percent of males and 46 percent of females know one or more ways of reporting a bribe. Similarly, in non - core districts 67 percent of males and 42 percent of females know one or more ways of reporting a bribe. Figure 3.33 shows the percentage of people knowing one or more ways of reporting a bribe at Endline . The percentage for core districts (54 percent) was almost identical to that for non - core districts (55 percent). The third Progress Assessment Survey (November 2018) identifies 95 percent of citizens in core districts as knowing about the 515 - phone numbe r. KII and FGD analysis suggests that the most cited method of reporting corruption is the 515 toll - free number with the mobile app and internet websites hardly mentioned during interview. A community leader in Koidu said the following about the PNB platf orm ‘ ’I think one of the advantages of the PNB campaign is that they have created a communication lines that can be easily accessed by someone to relay his/her information anonymously’’. An MDA staff member in Bo district said ‘’ I want to believe the prot ection given to those that make the reports of corrupt practices is one of the key things that is making the programme to succeed.’’ With respect to confidentiality, one Kenema community leader commented that “ we are also made to understand that the 515 li ne is free and the caller I.D number will not register at the call centre. When your call is put through you will now explain the incident and they will know what to do” . 23 Logframe indicator 2.3 63.2% 68.8% 47.6% 44.3% Core districts non-core districts Male Female 55.7% 56.5% Core district Non-core district

31. 27 Afrobarometer figures from the 2018 survey largely confirm the same trend: 52 percent of citizens nationwide said that levels of corruption had either stayed the same or decreased, compared with 16 percent in 2015. 30 Figure 3.37. Comparison of baseline districts with Endline core and non - core districts, in percentage of citizens thinking that corruption has increased/decr eased over the past year Figure 3.38 Comparison percentage of citizens thinking that corruption has increased/decreased/ stayed the same over the past year, at Endline , in core districts, by gender. Figure 3.39 Comparison percentage of citizens thinking that corruption has increased/decreased/ stayed the same over the past year, at Endline , in non - core districts, by gender. 30 Communication from CGG after a public presentation of the 2018 Afrobarometer figures in December 2018 70% 10% 5% 15% 39% 15% 39% 7% 32% 36% 28% 5% Increased Stayed the same Decreased Don't Know Baseline Endline Core Endline Non-core 26% 14% 13% 35% 8% 5% 25% 13% 18% 29% 6% 9% Decreased a lot Decreased somewhat Stayed the same Increased a lot Increased somewhat Don’t Know Male Female 7% 19% 39% 23% 11% 2% 9% 20% 34% 15% 15% 7% Decreased a lot Decreased somewhat Stayed the same Increased a lot Increased somewhat Don’t Know Male Female

36. 32 4.3. Knowledge of PNB According to FGDs with service users, bike riders and community leaders formed the majority of the persons interviewed in the core districts who knew about the Pay - no - bribe campaign. The most common knowledge about the campaign is that it sensitises citizens about their rights and encourages them not to pay bribes to service providers. The other mo st common information about PNB held by citizens in core districts was the knowledge of the 515 toll - free number. A complaint, however, was that sometimes people call and make a report, but they do not perceive any real actions being taken. 33 In non - core di stricts fewer people in FGDs have heard of PNB, and in Bonthe knowledge of PNB was lower still, which is to be expected. Those who knew about PNB stated that it was a campaign to stop payment of bribes and that they had heard about it through radio jingles . 4.4. Willingness to report FGD findings with bike riders in core districts indicate that they are willing to report corrupt practices on the 515 hot - line with most confirming that they already make reports. The challenge they highlight is in seeing litt le visible direct action taken against perpetrators. According to bike riders, they were very excited when they heard of the PNB programme and most have benefitted from PNB trainings and sensitisation, helping relatives, friends and other bike riders to u nderstand the messages and encouraging them to report corrupt practices. Some claim to report on a daily basis, and they ask questions on the ACC - PNB radio programmes, as well as make suggestions on corruption discussion topics. Their main concern relates to the MDA response to public reports of corruption. They continue seeing the same corrupt workers at check - points. Slow MDA responses are discouraging some bikers to continue to report as they consider it to be of no use since nothing will be done to perp etrators. 4.5. Benefits of PNB From FGD, citizens in core districts confirmed that the PNB programme has helped them to know their rights and this knowledge has enabled them to respond appropriately when situations involving bribery and requests for money arise. Most respondents in core communities claim that the PNB campaign has helped to reduce levels of petty corruption as police officers, nurses and teachers are more afraid to ask for money publicly than before. The paragraph below highlights some resp ondent comments on perceived benefits of the PNB programme. “For my level of understanding.... regarding pay no bribe, I believe I am in a better position now to challenge any policeman that wants to violate my rights” (A bike rider, Lumley). “I think PNB h as helped the government to reduce corruption and I believe if they continue like this the country will soon start developing” (A chief at Yardu, Kono) “In the past, parents report cases of teachers requesting money for the issuance of report cards. Sinc e the inception of the PNB in the district a drop in this [practice] has been realised, compared to the past”. (Local Council Staff, Kenema district) Similar comments were made by FGD and KII respondents in non - core districts. Local council staff in Koina dugu stated that the ACC has put in place structures, like integrity committees, to mitigate corruption in the sectors. This has drawn the attention of senior management to the issue of corruption at service delivery points. The PNB has thus helped to stre ngthen MDA accountability and this should be sustained. 4.6. Involvement in PNB implementation FGD respondents in core districts cited various levels of involvement in the PNB programme. Some respondents (c. 20 percent) confirmed their participation in se nsitisation meetings organised by civil society 33 As noted above, the PNB model encourages systemic improvements by MDAs rather than direct act ion against perpetrators.

8. 4 be less interested in active engagement than the non - core districts, for whom the PNB topic is fresher and whose cit izens are happier to engage at this stage. The worrying use of sexual favours in lieu of money came through strongly in the survey, particularly in the education sector. The slogan “use what you have so that you can get what you want ” was cited by an olde r, male bike - rider in Kailahun. Section 1: Introduction 1.1 Background and context of the PNB “... i f you ask them about the free medical, they will tell you if you are waiting for the free medical, you will have free die” . The DFID funded Anti - Corruption Support to Sierra Leone programme seeks to tackle both the petty corruption that citizens encounter on a daily basis and grand corruption, which affects Sierra Leone’s progress out of poverty. One of the key components of th is programme is the development of the Pay No Bribe (PNB) website and mobile application with the Anti - Corruption Commission (ACC) of Sierra Leone. The PNB Campaign is a Government of Sierra Leone (GoSL) initiative, led by the ACC and implemented in colla boration with relevant Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) and has been running since 2016. The PNB platform is a reporting mechanism enabling citizens to anonymously report incidents of petty corruption and bribery. The platform is designed to co llect reports on bribery and corruption in six service sectors: Education, Electricity, Health, Police, Water, and from May 2018, the Judiciary; to provide a database on petty corruption and bribery trends to support the work of the ACC and to feed into ev idence - based policy and decision making. The system specifically targets the points of service delivery that are prone to petty corruption and where demands for small payments impact heavily on the poorest and most vulnerable, including the rural poor and growing numbers of urban poor. This programme has established three key channels for citizens to report petty corruption, namely, a toll - free 515 number, a mobile phone application and an internet website. Through these channels, citizen can anonymously r eport incidents of petty corruption in real - time. These reports are compiled and discussed periodically (monthly) with the respective sectors and districts in ACC led Technical Working Group meetings, who are then encouraged to take the necessary actions t o prevent future occurrence of the incidents. The programme also works with the print and electronic media to increase the quality and quantity of media coverage of corruption in basic services using the published results as a platform for debate. Civil Society Organisations carried out outreach, as d id the ACC Regional Offices. The programme conducted a baseline survey in 2016 in four pilot PNB districts (Bo, Kenema, Bombali, Western Area Rural + Urban) and two non - pilot districts - Bonthe and Koinadugu. The baseline survey employed both qualitative and quantitative methods to fill information gaps around specific logframe indicators. 1.2. Purpose and scope of this Endline survey The overall aim of this Endline survey was to provide robust qualitative and quantitative information on the Pay No Bribe (PNB) programme, against which the progress of the programme over the last two years can be assessed. The Endline survey garnered information to establish the following Logframe indicators: • Impact Indicator 1: Percentage of people across Sierra Leone who paid for service that are supposed to be free or paid a bribe in the last 6 months and to access a) water and sanitation b) ‘free’ treatment at local health clinic or hospital c) school placement/exams/report card; d) power; e) police; or f) justice se ctor. • Outcome Indicator 1: Percentage of people thinking that the news media are effective in revealing government mistakes and corruption.

13. 9 It is interesting that the survey indicates higher levels of bribery reported at Endline than at baseline in core districts; some of the factors underpinning this are discussed in the Executive Summary pages 5/6. According to figure 3.4, a number of people said that they are still paying but are paying less ofte n now than before: 32 percent of people stated that they have paid less frequently; 45 percent that payment intervals have not changed; and 19 percent that they are paying more often now than before. The DMO in Bo said that most of the corruption allegati ons against health care workers are false. He stated that, “At the health facility we have the Free health care drugs that are free, and the cost - recovery drugs that are not free. Whenever the free health care drugs finish and free health care patients are asked to pay for the cost recovery drugs, the patients complain that the health worker is being corrupt” . Discussions in focus groups indicate that there is lack of clarity over whether payments for drugs are cost recovery or not, and payment for cost re covery drugs can be confused with bribery. Figure 3.5 suggests that slightly more males than females report paying small amounts at a health facility in both core and non - core districts. This is not surprising because in most families in Sierra Leone, it is the husband/head of the household that bears the most cost. Further analysis of the quantitative data revealed inter - district differences in payment of bribes for health services. In core districts, the district reporting the lowest level of bribe pay ing for services was Bombali (2 percent) and the highest was Kono (64 percent). Qualitative information from Kono appears to support this, indicating that people were less convinced that there had been changes in bribe paying behaviour although the ACSL s econd Progress Assessment Report 10 records much less variance: between 29 percent and 35 percent of citizens in Bombali, Bo and Kono stated that health officials had stopped asking for bribes. The main variances highlighted in the Progress Assessment Report are local, e.g. only 12 percent of citizens in Kenema urban community observed that health officials had stopped asking for bribes, which was significantly lower than urban areas in other core districts, all of which scored more than 20 percent. In this i nstance, the PNB team was informed that the health IMC in Kenema had not been functioning and that Kenema Government Hospitals were experiencing significant challenges with supply shortages. The third Progress Assessment Report indicates that 32 percent of people t hought that Health officials had stopped asking for bribes, compared with 16 percent in non - core areas. In non - core districts the Endline Survey indicates that the highest level of bribe payment was in Pujehun district (63 percent) and lowest in Koinadugu (33 percent). The reasons for these inter - district differences are not clear from the qualitative analysis, but Pujehun is a less visited area which may mean that citizens there have been less exposed to PNB messages. Generally, the Endline Survey FGDs an d KIIs indicated that citizens were seeing some changes in behaviour of health officials, even if they hadn’t completely stopped asking for bribes. The issue is further complicated, however, by the sale of drugs at cost recovery prices, which happens when a health centre has run out drugs covered under the free health care scheme. Patients appear to be not to be clear on what the charges are for and whether or not they are legitimate. Figure 3.3 Comparison of baseline with Endline core districts and Endli ne non - core districts, of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to access health care services at a health facility. 10 See www.pnb.gov.sl and footnote 3 above

24. 20 constantly been provided with regular information on PNB through various channels for over 2 years and citizens may this have lost some enthusiasm from when they initially heard about the programme. Figure 3.27 compares the percentage of people aware that ordinary citizens can make a difference in fighting corruption in core and non - core districts at Endline . Percentages were 68 percent, 74 percent, and 76 percent, in core , non - core and Bonthe districts respectively. According to findi ngs from the KII and FGDs, some people in core districts described the PNB actors as slow in responding to the reports they send. It appears that many respondents did not know how the PNB team used the reports received from citizens and expect direct and v isible disciplinary action against perpetrators. 21 Figure 3.26 indicates more males than females aware that ordinary citizens can make a difference in fighting corruption in both core and non - core districts (about 71 percent of males and 65 percent of fema les in core districts about 79 percent of males and 69 percent of females in non - core districts). FGDs and KIIs also investigated the role of ordinary citizens in fighting corruption. Quite a number of respondents agreed that petty corruption is a two - way act; the service user and the service provider are both responsible – if citizens refuse to give small payments then service officials wouldn’t expect any inducements. A number of reasons are identified for why petty corruption takes place, including the role of citizens themselves: • Service users pay bribes for service because they want or need the service. A community leader in Koinadugu commented that “You see what, we want to get quick favour from Government people and when you are plenty for it, you m ust bribe to get it before the others....” • Ignorance is also another reason for service user to take part in petty corruption. A bike rider in Waterloo said that "Because of high level of illiteracy and lack of knowledge in the country, people pay for servic es they should not pay for”. • When they do not have the necessary requirements for a job, people become involved in petty corruption. A community leader in Tonkolili district said ‘’When people are unqualified for a service, what do you expect? They pay something to be considered for a post” This suggests that if citizens are prepared to wait their turn and are informed about correct charges, then service providers will have fewer opportunities to ask for small payments. In KIIs and FGDs, respondents suggest that because people have been reporting bribes, service providers are not requesting small payments as much, and that citizens also may be less inclined to make payments. This indicates a growing citizen awareness that people themselves can help to reduce corruption by reporting it to relevant authorities. This was summarised by a service user in Bo: “ One possible consequence of the PNB is that it creates fear, the fear that if you commit corruption, somebody who may have seen you will report you wi thout your knowledg e”. A community leader in Tonkolili district commented “ ...the people are now aware that public services are free and should not be paid for” A local service user in Koinadugu said “Now PNB has given us more strength to fight against corru ption”. Figure 3.25. Comparison of baseline and Endline in percentage of people who are aware of how ordinary people can make a difference in fighting corruption. 21 PNB strategy is to use the information to bring about system - wide changes in the sector. 32% 16.9% 67.9% 73.6% Core districts Non-Core districts Baseline Endline

41. 37 Annexes Annex 1. Detailed survey and field work procedures Field Work Thirty four trained research associates (23 Enumerators and 11 supervisors) were organized into district teams and teams departed on Monday August 13 th . Assessment Methodology Study Sites The Evaluation was conducted in: • The 6 PNB core districts ( Bo, Kenema, Bombali, Kono and Western Area rural and Urban) • 4 non - core PNB districts (Koinadugu, Pujehun, Kailahun and Tonkolili) • Bonthe, where there has been limited activity Methods A Mixed - method approach were used for data collection, combining quantit ative with qualitative methods. Specifically: • Household Survey - Quantitative • Focus group discussion – Qualitative • Key Informant Interviews – Qualitative The tools for this evaluation were those used for both the baseline and midline assessment of the proje ct. Prior to commencement of the field work, the tools were reviewed by Dalan team and later field tested by a team of experienced enumerators. Issues emerging from the field - testing exercise were addressed by the Coffey team. The draft questionnaire was u sed to train enumerators, who again piloted the tools within communities in the Western Area that were not used for the main Endline survey. Comments from the pilot were also addressed prior to finalisation of the tools and commencement of field work. Household survey Description of Sampling Procedure The recommended sample sizes were 560 for core districts, and 450 for non - core and Bonthe districts. A purposive sampling approach was used to establish the communities to be surveyed. The sample sizes were distributed using a PPS method. Individual communities were therefore used as the unit of sampling, so that data will be collected within designated core and non - core communities. For Core communities two levels of PPS sampling procedure were used firstly to determine the number of households to interview in each district, and then to determine the chiefdoms in which data will be collected. The first level of PPS sampling determined the number of households to interview in each district, using the 2015 population estimate provided by Statistics Sierra Leone census data. The total population of the intervention chiefdoms was then used as a b asis for district level PPS sampling to determine the number of households to interview in each core district. (See Table A1 below). The second level PPS sampling was used to determined chiefdoms in which data will be collected. Based on total population of intervention chiefdoms in each district, the PPS sampling technique was again used to determine the chiefdoms in which data for the assessment will be collected. After selecting the chiefdoms, random sampling technique was used to select the communiti es within these chiefdoms that will be used for the survey. For the core districts, it is recommended that 80 percent of the communities for the assessment should be those where PNB implementation has been on - going since 2017 and 20 percent should be comm unities where intervention started between April and June 2018.

29. 25 Figure 3.35 Comparison of percentage of citizens claiming a) to have listened to/read information on anti - corruption in the previous 3 months; b) to have had a discussion about corruption with family/friends in the last 3 months, at Endline in core and non - core districts, by gender. Figure 3.36 Comparison of core, non - core and Bonthe district in percentage of citizens claiming a) to have listened to/read information on anti - corruption in the previous 3 months; b) to have had a discussion about corruption with family/friends in the last 3 months, at Endline. The focus group discussions and KIIs in both core and non - core districts raise nuanced perspectives on this issue. In non - core districts, comments from participants in focus groups largely support t he survey findings, i.e. that they listen to and discuss corruption regularly with friends and family. For example, a market woman in Pujehun claimed “ I talk about it much in the house than last year because the business is rough now [more] than last year. “ Similarly a Bike rider in Kailahun stated “ I usually discuss those messages with friends and relatives every day ”, and a man from Koinadugu claimed “ I ... discuss with my children at home about petty corruption.” One man, a farmer, stated that as a farmer he didn’t get involved in corruption and was not available to listen to radio programmes because he was out in the fields. In core districts, people also appear enthusiastic about discussing corruption issues with friends and family, perhaps more than the survey findings would indicate. Typical comments include “ I try to educate my family that anyone who asks them to pay bribe, don’t pay, whether from school, police station etc .” (market woman, WA Rural); and “ Sometimes when I’m listening to the radio and t here is a programme on corruption, I ask my kid and wife to join me to listen to it” (man, Bo rural) . What was also clear from core district focus groups was that discussions also take place in the workplace such as the market or among bike riders: “ In our homes it [discussion on corruption] is almost always with our wives and children. With our union members this is done during resting time while they are waiting for passengers” (male bike rider, Bo town). Interestingly, the third Progress Assessment Surve y 27 also records higher numbers of citizens claiming to have discussed corruption with family and friends in core districts (75 percent), compared with 80 percent of citizens claiming to have listened to or read information about corruption. 27 See http://www.pnb.gov.sl/ and footnote 3 above 80.4% 35.4% 85.8% 52.8% 65.2% 29.7% 79.5% 41.5% Listened Disccused Listened Disccused Core districts Non-core districts Male Female 73.1% 82.7% 62.0% 32.5% 47.2% 41.0% Core district Non-core district Bonthe district Listened Discussed

11. 7 2.4 Summary of the PNB fieldwork processes The fieldwork for the PNB Endline survey was conducted by Dalan Development Consultants, a national consulting agency in Sierra Leone. Dalan worked closely with the Coffey ACSL team for the Endline survey. ACSL were responsible for agreeing the methodology used for the survey (which was comparable with the baseline and midline surveys), designing FGD and KII frameworks and for conducting interviews with ACSL partners. Dalan was responsi ble for finalising the methodology, identifying the PNB core and non - core communities, recruiting enumerators and supervisors, training, planning, implementing and overseeing day - to - day fieldwork and quality assuring the data, as well as for carrying out F ocus Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs). Annex 1 provides a detailed description of the methodology and fieldwork processes. 2.5 Data Analysis Quantitative data was captured using a mobile data application and the data was hoste d in the web on a daily basis. The final data was analysed using both pivot tables in Excel and cross tabulations in SPSS, to generate the required tables and graphs. Comparative analysis for all key variables was done to assess the change between baseline and Endline scores, as well as assessing differences between core and non - core districts. The results are presented in tables and graphs. In all, there were 93 qualitative scripts generated from the field work (56 FGDs and 37 KIIs). The qualitative data, recorded on tape, was transcribed from local languages into English by experienced transcribers with the supervisors/enumerators who engaged in field work. The English language scripts were analysed by theme, guided by an appropriate coding framework. Det ailed tables for all log - frame indicators are provided in Annex 2 of this report. Section 3: Key Findings 3.1 Demographic characteristics of respondents. The survey had a sample size of 1,009 compared to 1,122 respondents for the baseline survey conducte d in 2016. A total of 511 (51 percent) of the respondents in the Endline survey were male while 498 (49 percent) were females. About 62.5 percent of respondents were from urban localities while 37.5 percent were from rural localities. Age distribution of t he respondents in the Endline survey was as follows: 18 - 35 years=41 percent; 36 – 54 years=40 percent; 55 years and over=19 percent. 3.2. Detailed Endline Findings by Log frame Indicator: Impact Level The following discussion refers to Impact indicator 1. 3.2.1. Payment of bribe in water sector. Respondents were asked whether they have paid a bribe to access services in the Water, Education, Health, Power, Police and Judiciary sectors in the 6 months prior to the survey. Figures 3.1, 3.3, 3.8, 3.13., 3.16 and 3.18 compare results obtained at baseline with those obtained at Endline in core and non - core districts for each of the sectors. A total of 252 respondents from districts with pipe borne water (provided by government or community) were asked if they h ave paid a bribe to access water services in the 6 months prior to the survey. Figure 3.1 shows that the percentage of people who paid a bribe in the 6 months prior to the survey in the water sector in core districts reduced from 42 percent at baseline to 6 percent at Endline . Figure 3.2 shows a comparison of the percentage who reported paying a bribe in the 6 months prior to the Endline survey by gender. The figure shows that 3.8 percent of males and 9.2 percent of females, respectively, reported that the y paid a bribe the 6 months prior to the Endline survey to access services in water sector. Nobody paid a bribe in the

20. 16 Figure 3.17. Comparison of the percentages of people who paid a bribe in the last 6 months to police at Endline in core and non - core districts, by gender. There are a number of factors characteristic of the police that do not apply in the same way to other sectors, but which mean that the messages coming from the police sector may appear confusing or contradictory. Firstly, the nature of bribery is different: bike riders (among others) complain about the bribes demanded by police, but unlike other sectors, 13 bribes are also paid in order to avoid legitimate fines for something that a person is doing that is illegal, such as driving without a licence, driving a vehicle in bad condi tion or riding a motorbike without wearing a helmet. In FGDs, all of the bike riders confirmed that they paid bribes to police to avoid being fined or jailed for these offences. Thus, there are some circumstances in which drivers/riders would want to conti nue paying bribes to police and would not necessarily want to see the government as willing to act on corruption. Secondly, the citizens who engage with the police most frequently are the bike riders. Bike riders tend to be younger and male, they have mobi le phones, have engaged actively with PNB, and have reported illegal police actions (such as checkpoints) in large numbers. 14 FGDs indicated that motorbike riders have challenged the police over requested bribes and have monitored police responses to PNB r eports such as removal of checkpoints: riders have also reported increased caution on the part of police in receiving bribes. However, motorbike riders have expectations of immediate behaviour changes/ movement of staff/other punishments 15 as a result of re porting to PNB that are not always met, and they complain loudly in focus groups when this doesn’t happen. FGD findings also revealed that many people in core districts were of the opinion that the police were not responsive enough and that PNB has not do ne enough in terms of responding to reports about the police and acting upon them. Riders said, for example, that they continue seeing corrupt officials at check - points even after the officials have been reported. This relates partly to the desire to see i mmediate changes noted above, and partly to a lowering of enthusiasm when some early changes by police are not sustained. On the other hand, bike riders in non - core districts expressed stronger enthusiasm about the police and PNB, and they described it as a very good programme for stopping petty corruption. This may be because they are relatively new to PNB and hopeful that they will see changes. In both core and non - core districts, the levels of active engagement by bike riders are higher than engagement by citizens in other sectors. 3.2.6 Payment of bribes in the Justice sector. The Judiciary was not among the initial intervention sectors, 16 and so had no 2016 baseline. A comparative study of Endline against baseline has thus not been possible. Figure 3 .19 compares Bonthe district, core and non - core districts at Endline , in the percentage of people who paid a bribe to judiciary. According to the figure, 4 percent, 4 percent and 15 percent of people in control, core and non - core districts respectively, pa id 13 Except judiciary 14 See also the ‘Willingness to Report’ section under 4.4 15 Immediate punishment/removal/relocation of staff is outside of the theory of change of the PNB, although it has happened occasionally in all sectors. 16 The MOU between the Judiciary and PNB was signed at the end of 2017, but engagement between the Justice Sector and PNB has been minimal: IMCs have not been set up, and service charters have not been provided. In the end, the Justice sector was inc luded i n outreach over the last 8 months of PNB, but with limited emphasis. Few changes can be expected in these circumstances. 21.4% 43.2% 10.3% 21.0% Core districts Non-core districts Male Female

25. 21 Figure 3.26 Comparison of p ercentage of people who are aware of how ordinary people can make a difference in fighting corruption, at Endline in core and non - core districts by gender. 3.5. Perception on the ease of reporting bribe via website, call Centre and PNB App. The pay - no - bribe campaign established three key channels for citizens to report petty corruption; a toll - free 515 mobile number, a mobile phone app, and an internet website. 22 Figure 3.28 provides comparative baseline and Endline for Core and non - core districts with the percentage increasing from 21 percent at baseline to 56 percent at Endline in core districts, and from 16 percent at baseline to 57 percent at Endline in non - core districts. Figure 3.29 indicates that 63 percent of males and 47 percent of females in core districts reported that it was easy to use the platform s for reporting corruption. Similarly, in non - core districts 69 percent of males and 44 percent of females reported that it was easy to report a bribe. Figure 3.30 presents a comparison of core and non - core districts in percentage of citizens who state th at it is easy or fairly easy to report a bribe via the website, call centre or app, at Endline . The figure shows that equal proportions of people in core (56 percent) and non - core districts (57 percent) stated that it was easy to report using the reporting platforms. FGDs also confirmed that using the 515 toll - free number is easy. A service user in Kailahun said “The PNB told us that we should not give money to teachers for report cards, practical or pamphlet and that was the time they told us of the 515 free line”. Another service user in Bo District reported that “When someone is asked for money in the education office you will call 515 and make a report”. This clearly indicates that people can easily recall the toll - free number for reporting petty corruption. Figure 3.28. Comparison of baseline and Endline in percentage of citizens in PNB targ et areas who state that it is easy or fairly easy to report a bribe via the website, call centre or app. 22 Logframe indicator 1.3 70.9% 79.0% 64.9% 68.2% Core districts non-core districts Male Female 21% 55.7% 16.00% 56.5% Baseline Endline Baseline Endline Core district Non-core districts

28. 24 who discussed corruption with friends and families increased from 15 percent at baseline to 47 percent at Endline . Figure 3.36 compares the percentages of people across Bonthe district, core and non - core districts, who listened to items abou t corruption on the radio and/or discussed it with friends and families in the 3 months prior to the Endline survey. The figures indicate that 73 percent, 83 percent and 62 percent of people in core, non - core and Bonthe districts respectively listened to m essages about corruption in the 3 months prior to the Endline survey. Similarly, 33 percent, 47 percent and 41 percent of people in core, non - core and Bonthe district respectively discussed corruption with someone in the 3 months prior to the Endline surve y. This result suggests greater inclinations to listen to news about corruption than to discuss the issues. With respect to gender, Figure 3.35 indicates that more males than females listened to and discussed issues on corruption in both core and non - core districts. This can no doubt be explained by great male radio ownership and access. Analysis of issues discussed in focus groups revealed concerns about the Presidential Transitional Team (PTT) report, 25 Hajj - gate 26 , bribe taking by teachers and health work ers and other issues relating to corruption in government offices. It appears that there are significant inter - district differences in the percentages of people who listened to or discussed issues of corruption with friends and family. In core districts, Bombali citizens reported listening to and discussing corruption the most and Kono and Kenema citizens listened and discussed corruption issues the least. It is not clear why this is the case. Figure 3.34 Comparison of baseline and Endline in core and non - core districts in percentage of citizens claiming a) to have listened to/read information on anti - corruption in the previous 3 months; b) to have discussed corruption with family/friends in the last 3 months 25 The PTT report was produced soon after the new President came to power in 2018. It claimed that the poor state of the economy was due the “astonishing level of fiscal indiscipline”, “frantic looting”, “politically organised racketeering” of the previous government 26 Hajj - gate occurred when funds meant for over 500 Muslims to perform a pilgrimage to Mecca, were allegedly misused by government officials. This brought a lot of shame to the would - be pilgrims and was a debate that took national dimensions. It was alleged that several very highly - placed government officials were involved, including the then Vice President of Sierra Leone, who was the Chair of the Hajj committee. 73.3% 36.5% 27.4% 14.9% 73.1% 32.5% 82.7% 47.2% Listened Discussed Listened Discussed Core districtxs Non-core districts Baseline Endline

30. 26 However, there were also comments suggesting that perhaps corruption was being discussed less levels had reduced “That is true because it [corruption] has reduced now so we talk less about it than last year” (man service user, WA rural). Participants also noted that where there is more employment, corruption may be discussed less with families “ some people have radio, but they don’t have that time to sit and listen to it because of the type of job he/she migh t be doing” (male service user, WA urban). A participant from Kenema town commented that with wider knowledge of corruption, family members keep quiet because they suspect that corruption by other family members is what is putting food on the table, and if they mention it there will be less food: “ and at the end of the day that family will be deprived of their daily ration of food for that day. This is what happens amongst families and friends that make people not to talk about petty corruption.” (woman, Ke nema town). 3. 8. Citizens perception on the changes in levels of corruption in the past one year. The survey captured citizen’s perception of corruption levels relative to the previous year. 28 According to figure 3.37, the percentage of citizens reporting that corruption levels have either decreased or stayed the same relative to the baseline was higher for Endline core and non - core districts. This is significant, as it suggests that citizens themselves are beginning to experience a reduction in petty corruption. KII and FGD findings clearly state that corruption has reduced drastically in some sectors, but that there is more work to do to further reduce corruption. One bike rider stated that “The PNB has made police not to publicly collect money again. But bribery is still going on, because he will take you to a corner and there he will take money from you”. FGD findings also reveal that the PNB campaign has created awareness among service us ers and service providers through the availability of the 515 toll - free number to report corrupt practices. The platform has instilled doubts in the minds of some service providers, which may have led to a reduction in the rates of petty corruption among t hem. KIIs and FGDs also highlight that the behaviour of service delivery officials has changed: even in cases where they are still accepting bribes, they may be asking for smaller amounts and/or asking less often. The conclusion of the second and third PNB Progress Assessment reports 29 are similar, i.e. that the PNB Campaign has been more effective in the Provinces than in Western Area, probably due in part to the fact that service providers in the districts engaged in PNB - led Regional Technical Working Groups and Accountability Forums. These helped strengthen transparency and accountability close to the level of service delivery: in contrast, Western Area engagement was with MDA HQ offices which proved to be more distant from actual service delivery. The reports also note, however, tha t perceptions of public service delivery in WA have improved, but not as much as the provinces. Figures 3.38 and 3.39 compare perceptions of corruption at Endline in core and non - core districts, respectively, by gender. Both figures show that slightly mor e males than females believe that corruption has increased. About 43 percent of males compared to 35 percent of females of females believe that corruption has increased, in core districts. Similarly, 34 percent of males compared to 30 percent of females in non - core districts believe that corruption has increased. This may reflect the fact that the police are generally considered the most corrupt and more men than women have contact with them. Figure 3.40 compares citizen’s perceptions on corruption at Endli ne for core and non - core districts. According to the figure, the percentage of people who said that corruption has either decreased or stayed the same compared to the previous year was 64 percent in non - core districts, 60 percent in Bonthe district and 54 percent in core districts. It is interesting that 60 percent of people in Bonthe district claimed that corruption has decreased or stayed the same even though no proper PNB intervention has taken place in the district. This could be because of some informa tion on PNB trickling into the district through posters or radio shows, or through Bonthe residents being exposed to PNB in other areas. 28 N o logframe indicator. The ACC requested the inclusion of this question in March 2017 29 See www.pnb.gov.sl and footnote 3 above